For example, it is very difficult to measure the enthalpy change (ΔH) for the combustion of graphite to carbon monoxide (CO) because some carbon dioxide (CO2) is always produced, as shown in the equation below:

However the enthalpy change (ΔH) for the combustion reaction to form only carbon monoxide is very easily worked out using Hess's Law.

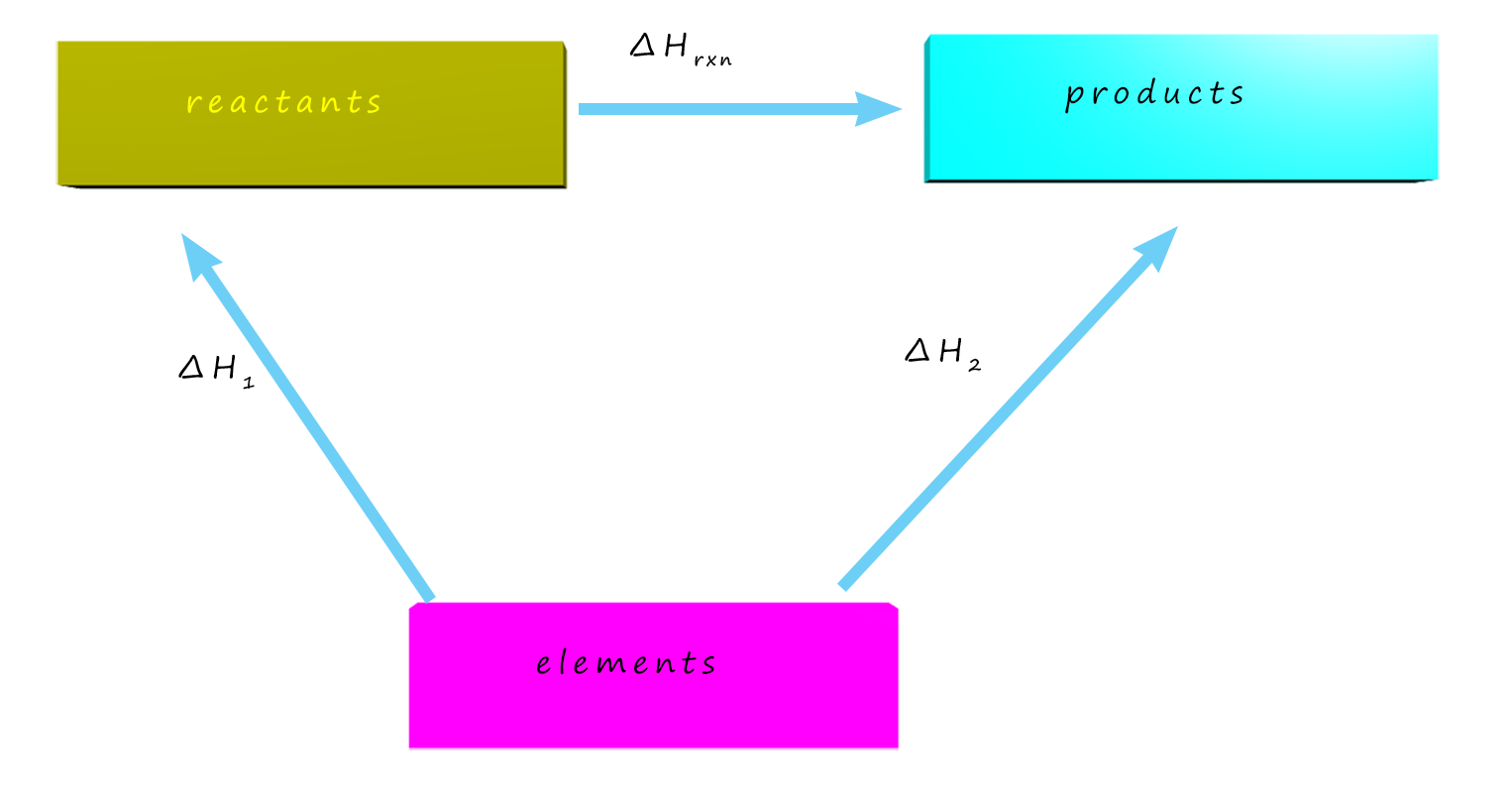

So what exactly is Hess's Law? Well it is simply an extension of the law of conservation of energy; which states that energy cannot be created or destroyed but only changed from one form to another. As an example consider the diagram opposite, here the enthalpy change (ΔH1) for the reaction A→B is an exothermic reaction with an enthalpy change (ΔH1) of -1000 kJ.

Now imagine that for some reason the reaction A→B cannot be carried out directly. However the changes A→C and C→B are possible; these two reactions have enthalpy changes of ΔH2 = -400 kJ and ΔH3 = -600 kJ. Now the reaction A→B is not possible so its enthalpy change cannot be measured experimentally, but we can still calculate the enthalpy change for this reaction by taking the roundabout route. Instead of going directly from A to B simply go via an intermediate route, that is through C. The important fact is that both routes start at A and end at B, that is the starting and finishing points are the same. This means the change in energy or enthalpy depends only on the "start" and "end" points of the reacting system, much like your change in altitude when you climb a hill or mountain: between the base and the peak of a mountain your change in altitude is the same whether you climb straight up the mountain or take a winding path to the top. In essence this is Hess's Law.

Hess's Law states that:

The enthalpy change for a reaction depends only on the initial and final states of the reaction and is independent of the route by which the reaction occurs.

So in our example:

Or we could write this as ΔH1 = ΔH2 + ΔH3, that is ΔH1 is the sum of ΔH2 and ΔH3.

So here we can see that ΔH2 + ΔH3 = -1000 kJ, the same enthalpy change as ΔH1.

As long as the start and end points are the same, the overall enthalpy change

is the same. That’s all there is to Hess's Law!

In your exam you are likely to be asked to calculate the enthalpy change for a reaction using either enthalpies of combustion (ΔcHo) or enthalpies of formation (ΔfHo) data. If you are not sure what these enthalpy changes represent then pause for a moment and click the links above to do a little research before continuing.

| substance | Enthalpy of combustion / kJ mol-1 |

|---|---|

| C(s) | -394 |

| H2(g) | -286 |

| CH4(g) | -890 |

All the questions you are likely to be asked to solve using enthalpies of combustion data are all done in the same way. So follow the method below and you really cannot go wrong!

Problem 1 - Calculate the enthalpy of formation of methane (CH4(g))

using the enthalpies of combustion given in the table opposite.

Step 1 - You must write the equation for the reaction you are being asked to calculate the

enthalpy change for. In this case we have to calculate the enthalpy of formation of methane.

An equation for this enthalpy change is given below:

To calculate this enthalpy change we have been given enthalpies of combustion data. To be able to work out the required enthalpy change you need the enthalpies of combustion of all the elements and compounds present in the equation above; a quick check in the table shows that you have all the enthalpies of combustion data you need. Now all we need to do is draw a simple energy cycle using the data we have. Sometimes students get confused on how to start these cycles off, but if you are using enthalpies of combustion, which we are in this example, then the cycle goes downwards from the equation above. This is set out below:

1. The equation on the top line represents the enthalpy of formation of methane. This is the equation we have to calculate the enthalpy change (ΔH) for.

2. Since we are using enthalpies of combustion data to solve this problem we need to start by combusting each of the reactants, the carbon and the hydrogen. This combustion reaction will form carbon dioxide gas and liquid water. Remember that standard enthalpies have substances in their standard states and the standard state of water at 25oC is a liquid.

This is set out in the diagram shown. Here the downwards arrow shows 1 mole of carbon burning to form carbon dioxide gas; this represents the combustion of carbon and is labelled as ΔH1. This combustion reaction has an enthalpy change (ΔH) of -394 kJ mol-1. We are also combusting 2 moles of hydrogen to form 2 moles of liquid water; this is shown as: 2ΔH2 = 2 × (-286) = -572 kJ. I have not shown the oxygen needed for these combustion reactions but you can add this to the downwards arrow if you think it is helpful; it is not needed because the oxygen cancels out in the cycle.

So far the Hess's Law cycle is only half done. We have combusted the reactants. Now to complete the cycle all that is needed is for the product, methane in this case, to be combusted. Methane (CH4) is a hydrocarbon and it will burn (combust) under standard conditions using oxygen to form 1 mole of carbon dioxide gas and 2 moles of liquid water. Exactly the same products as we have for the combustion of the reactants in the equation above. Again I have not added the oxygen, as this cancels out in the cycle. This makes sense since in a chemical reaction we are rearranging atoms; no atoms appear or disappear. The combustion of methane, which we will call ΔH3, releases 890 kJ of energy. We now have:

Always ask yourself:

If you are given enthalpies of combustion,

👉 start by combusting the reactants.

This means the Hess cycle goes downwards to CO2 and H2O.

⚠️ Oxygen is often not shown — it cancels out.

So according to Hess’s law. As long as we start and end at the same place the sum of any enthalpies should be the same. So:

Note: We have to subtract ΔH3 because we are going against the arrow in taking the "long way" round in going from the reactants to the product methane.

The other type of problem you are likely to meet is where you have to use enthalpies of formation to calculate an enthalpy change.

| substance | Enthalpy of formation / kJ mol-1 |

|---|---|

| NH3(g) | -46 |

| NO(g) | 90 |

| H2O(l) | -286 |

As before the first step is to write out the equation for the reaction you have been asked to find the

enthalpy change for.

Example 2 - Calculate the enthalpy change for the following reaction using the

enthalpy of formation (ΔfHo) data in the table.

As before in order to calculate the enthalpy of reaction (ΔrxnH) using the enthalpy of formation data provided we need to

know the enthalpy of formation (ΔfH) for all the substances in our equation. Looking at the table we have all the

information we need, remember the enthalpy of formation of an element is by definition 0, which explain why no data is provide for oxygen in the table.

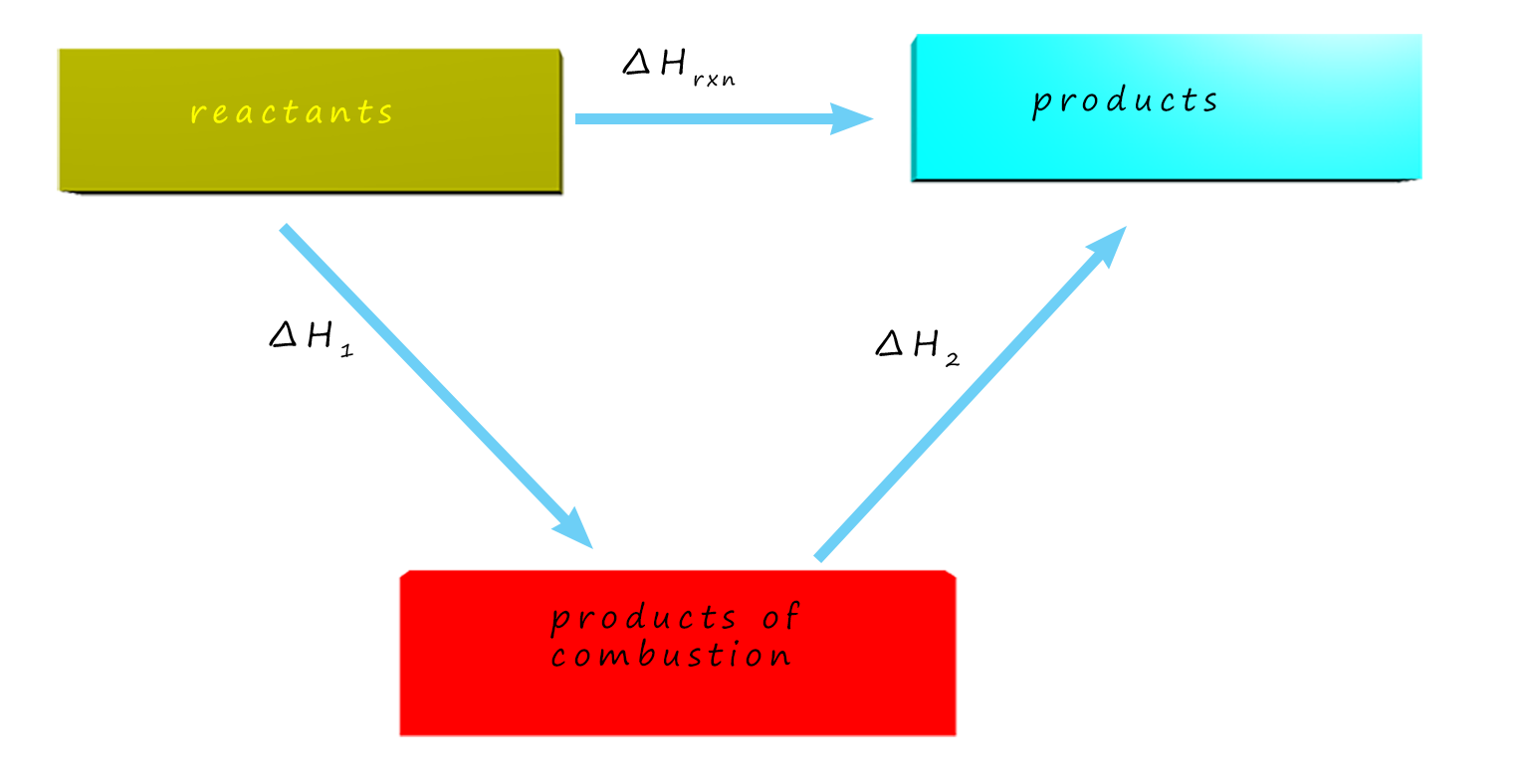

When we drew the energy cycle above using enthalpies of combustion (ΔcHo) we drew the cycle

"downwards" from our equation. This time using enthalpies of formation (ΔfHo) we

will work "upwards" towards the equation we have to calculate the enthalpy change for.

So we have:

Now there are 4 moles of ammonia in the equation we need to find the enthalpy change for so we will need to multiply this equation by x4 to account for the formation of these 4 moles of ammonia, lets call this enthalpy change ΔH1. So we have:

Now to complete the Hess's Law cycle simply calculate the values for the enthalpy changes when the products form from the reactants as shown in the image above.

This time we have to form 4 moles of NO(g) and 6 moles of water (H2O(l)):

So we have:

This is the equation for the ΔfH of NO. It will have to be multiplied by 4, since there are 4 moles of nitrogen monoxide gas produced.

Let's call this enthalpy change ΔH2.

We also form 6 moles of liquid water; an equation to show this enthalpy of formation will be:

This is the equation for the ΔfH of H2O. It will have to be multiplied by 6. Let's call this enthalpy change ΔH3.

Putting it all together we have:

So we can say:

So to get from the reactants to the products we go against the arrow for ΔH1, that is why it appears as -ΔH1 in the cycle above.

The hardest part of getting started with a Hess's law energy cycle is knowing where to start - remember that if you are given enthalpies of combustion data to calculate an unknown enthalpy change, your energy cycle goes "downwards" e.g.

If you are given enthalpies of formation data to calculate an unknown enthalpy change, your energy cycle goes "upwards" e.g.