As an example to explain what a disproportionation reaction is

consider the reaction that occurs when chlorine gas is dissolved in water.

An equation for this equilibrium reaction is shown below:

As an example to explain what a disproportionation reaction is

consider the reaction that occurs when chlorine gas is dissolved in water.

An equation for this equilibrium reaction is shown below:

The products of this reaction are the two acids hydrochloric and chloric (I) acid. Hydrochloric acid is a strong acid, that is one which fully dissociates in water while chloric (I) acid which is a weak acid (note in chloric(I) acid the I refers to the oxidation state/number of the chlorine), that is one which only partially dissociates in water. So we could rewrite the above equation to show all the ions produced when the chlorine goes into solution:

For each reaction:

1. Fill in the oxidation state of the highlighted element in each species.

2. Decide whether the reaction is a disproportionation reaction.

1) 3ClO– → 2Cl– + ClO3–

Element: Cl

Oxidation state of Cl in ClO–: in Cl–: in ClO3–:

Disproportionation?

2) 2HNO2 → HNO3 + NO + H2O

Element: N

Oxidation state of N in HNO2: in HNO3: in NO:

Disproportionation?

3) 3MnO42– + 2H2O → 2MnO4– + MnO2 + 4OH–

Element: Mn

Oxidation state of Mn in MnO42–: in MnO2: in MnO4–:

Disproportionation?

4) PCl3 + Cl2 → PCl5

Element: P

Oxidation state of P in PCl3: in PCl5:

Disproportionation?

We have seen above that when chlorine is added to water it reacts with it to form a mixture of two acids, the strong acid hydrochloric acid and the weak acid chloric(I) acid:

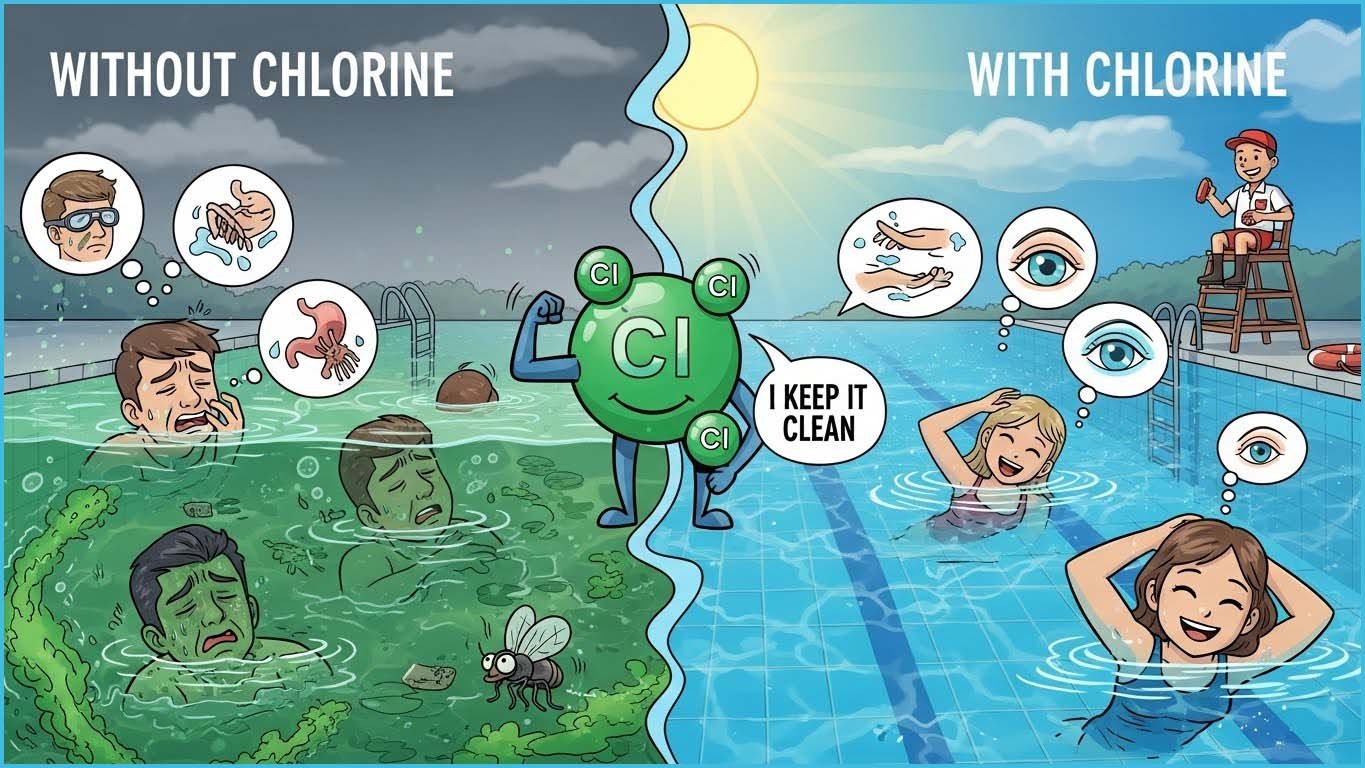

Out of these two acids it is the chloric(I) acid which is the real star of the show, chloric(I) acid is a powerful oxidising agent and it’s the reagent that does almost all the disinfecting and bleaching. The chloric(I) acid is the active disinfecting agent responsible for killing any harmful organisms present in the water to ensure it is safe to drink. In fact the chloric (I) acid is a more effective disinfectant than chlorine alone. It is highly effective at penetrating the cell walls of microorganisms, which allows it to easily diffuse through the cell membrane and once inside the cell the chloric (I) acid (HOCl) quickly oxidises the essential components of the cell such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, leading to cell death. This process effectively inactivates bacteria, viruses and some protozoa.

The concentration of chlorine in drinking water is around 0.7mg/dm3 though its concentration is higher in swimming pools. Swimming pools are carefully kept at around pH 7.2–7.4, this pH range gives a high proportion of the dissolved chlorine as chloric(I) acid (HClO), a very effective disinfectant and oxidising agent, while still keeping the water comfortable for swimmers and not too corrosive to pipes and fittings. If the pH drifts too high then more of the chlorine changes into chlorate (I) (ClO⁻ )ion which is much less effective at disinfecting the pool.

When chlorine dissolves in water it reacts reversibly to form hydrochloric acid and chloric(I) acid, the key disinfectant:

Cl2(aq) + H2O(l) ⇌ HCl(aq) + HClO(aq)

The chloric(I) acid being a weak acid then sets up a second, important acid–base equilibrium:

HClO(aq) ⇌ H+(aq) + ClO−(aq)

The two species in the equilibrium mixture behave very differently:

• HClO (chloric(I) acid) – extremely powerful disinfectant.

• ClO⁻ (chlorate(I) ion) – much weaker

disinfectant.

If pH drops, the concentration of H⁺ increases. Le Chatelier’s principle pushes the equilibrium to the left, producing more chloric(I) acid (HClO).

✔ Lower pH → more HClO → stronger disinfection. ✔ Higher pH → more ClO- → weaker disinfection. ✔ Swimming pools are kept at pH 7.2–7.4 to maximise HClO while avoiding water that is too acidic

However swimming pools cannot be run at very low pH values because if the water is too acidic it corrodes metal pipes and fittings, damages grout and perhaps the most important reason is it irritates swimmers’ eyes and skin, the bathers will probably not enjoy swimming in an acid! The 7.2–7.4 range is the ideal balance between comfort, safety and disinfection efficiency.

There is also the additional problem that if there is too much chlorine present in the water it can react with organic compounds found in the water and form organochloro compounds (see below for more detail) which are also very toxic and are also potentially carcinogenic. However if too little chlorine is added it may not necessarily kill all the potentially harmful microorganisms which may be present such as cholera, typhus and E.coli bacterium.

A similar reaction happens with bromine though the position of equilibrium lies much more to the left, an equation for this disproportionation reaction is shown below:

The products of this reaction are the strong acid hydrobromic acid (HBr) and the weak acid hypobromous acid, also called bromic(I) acid (HOBr). However, this equilibrium lies so far to the left that only tiny amounts of bromic(I) acid are formed. As a result, the solution remains brown because the concentrations of both HOBr and the bromate(I) ion (BrO⁻) are very low, these two substances are also both are too weak as oxidising agent to bleach the colour of the bromine water so it stays brown.

Iodine is for all practical purposes insoluble in water and does not undergo any of the disproportionation reactions that occur when chlorine or bromine are added to water. Although iodine is often dissolved in ethanol or a potassium iodide solution to form a solution called a tincture. This solution typically contains about 2-7% iodine and 2.4% sodium iodide or potassium iodide in alcohol and water. This solution is commonly used for disinfecting wounds and as a general antiseptic for skin infections.

Chlorine is added to drinking water primarily for its disinfectant properties. It helps to kill or inactivate harmful microorganisms that can cause diseases, making water safe to drink. The main reason why chlorine is added to drinking water includes:

Chlorine is added to drinking water primarily for its disinfectant properties. It helps to kill or inactivate harmful microorganisms that can cause diseases, making water safe to drink. The main reason why chlorine is added to drinking water includes:

We probably take it for granted that the water we get from our tap is safe to drink, however in many countries around the world this is not the case. There are many benefits to adding chlorine to drinking water, for example chlorine is highly effective at preventing many waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and typhoid fever. Chlorine also provides a residual effect, meaning it continues to disinfect the water as it travels through pipes and so preventing contamination of the water during distribution. The chlorination of drinking water is also a relatively inexpensive method of disinfecting our drinking water.

While chlorine is extremely beneficial for disinfecting water, there are some potential problems and dangers associated with its use, these include:

While chlorine is extremely beneficial for disinfecting water, there are some potential problems and dangers associated with its use, these include:

If you plan to use chlorine water in the lab it has to be freshly prepared. The reason for this is simply because if a bottle of chlorine water is left exposed to sunlight its pale green colour fades and oxygen gas is released according to the equation below:

This unwanted reaction can create problems, for example chlorine is added to drinking water to kill unwanted pathogens. Some of these pathogens can be a particular problem in swimming pools which is why chlorine is added to water used in public baths. However sunlight can cause the chlorine to leave the water reducing the amounts present. Therefore careful monitoring is needed to ensure that that the levels of chlorine are maintained at the correct level to ensure that any potential pathogens are effectively removed from the water.

We saw above that when chlorine (Cl2(g)) dissolves in cold water it forms a mixture of two acids: the strong acid hydrochloric acid and the weak chloric(I) acid.

This is a reversible reaction, so what happens if we add cold sodium hydroxide (a strong alkali) to this equilibrium mixture? Adding OH⁻ ions removes H⁺ ions from solution. According to Le Chatelier’s principle the equilibrium will initially shift to the right to replace the H⁺ ions that have been removed.

However, as soon as the acids are formed, the added OH⁻ ions immediately neutralise both HCl and HClO: HCl is converted into NaCl, and HClO is converted into sodium chlorate(I) (NaClO). This continual removal of the two acids forces the overall reaction even further to the right, producing the familiar products:

This is a disproportionation reaction. The oxidation state of the chlorine in Cl2 is 0. In the products, the chlorine has been both reduced to –1 in NaCl and oxidised to +1 in NaClO (sodium chlorate(I)).

This reaction is important because the mixture of sodium chloride and sodium chlorate(I) (sodium hypochlorite, NaClO) in solution is sold as bleach. The chlorate(I) (hypochlorite) ion (ClO-) is responsible for the disinfecting and bleaching properties associated with household bleaches.

Household bleach contains the chlorate(I) ion (also called the hypochlorite ion): ClO−. When an acid such as hydrochloric acid is added to bleach there is a number of reactions that occur. The first step is the formation of chloric(I) acid (HOCl), here the chlorate(I) ion simply accepts a hydrogen ion (H+) from the strong hydrochloric acid to for chloric(I) acid (note: the chlorate ion is simply the conjugate base of chloric acid(I):

ClO−(aq) + H+(aq) → HOCl(aq)

Chloric(I) acid is however unstable and it then reacts further with chloride ions already present in the bleach to form chlorine gas:

HOCl(aq) + Cl−(aq) + H+(aq) → Cl2(g) + H2O(l)

There are many documented incidents, including fatalities of cleaners being killed or seriously injured from mixing acidic cleaners with bleach and also of plumbers needing hospital treatment after breathing in chlorine gas while working on pipes containing bleach which had come into contact with acidic materials. There are also examples of restaurant workers and cleaners being killed by simply mixing acidic cleaners with bleach while cleaning floors which again resulted in the release of toxic chlorine gas.

✔ Adding acid to bleach releases toxic chlorine gas. ✔ This is why bleach must never be mixed with acidic cleaners such as toilet descalers or vinegar. ✔ The reaction is a classic example of chlorine chemistry and appears in the A-level specification.

Even small amounts of chlorine gas can irritate the eyes and lungs. In larger amounts it is highly dangerous, so mixing bleach with acid should always be strictly avoided.

If the solution containing chlorate (I) ions is heated then a further disproportionation reaction occurs and chlorate(V) (ClO3-) ions are formed

Here the chlorine has a +1 oxidation state in the chlorate(I) ion

(ClO-) while it is reduced to Cl- in NaCl and

oxidised to chlorine with a +5 oxidation state in the chlorate(V) ion (ClO3-).

If hot alkali sodium hydroxide is used instead of a cold sodium hydroxide solution then

a similar disproportionation reaction occurs but the chlorine is

oxidised directly to the chlorate(V) ion (ClO3-) missing out the chlorate(I) stage completely; an equation for

this reaction is shown below:

Exam practice in working out the oxidation states of elements. Click the button below and then work out the oxidation state of the elements shown in the four disproportionation reactions.

1) The decomposition of Hydrogen peroxide to form water and oxygen gas.

2H2O2 → 2H2O + O2

2) Copper(I) chloride disproportionation to form copper and copper(II) chloride.

2CuCl → Cu + CuCl2

3) Sulfur dioxide disproportionation to form sulfur trioxide and sulfur.

3SO2 → 2SO3 + S

4) The disproportionation reaction of nitrogen dioxide and water to form nitric acid and nitrous acid.

2NO2 + H2O → HNO3 + HNO2

A very common A-level question involves explaining why making bleach from chlorine involves a disproportionation reaction. Students often forget that chlorine gas reacts in two different ways at the same time.

When Cl₂ reacts with cold, dilute sodium hydroxide, it forms a mixture of chloride ions (Cl⁻) and chlorate(I) ions (ClO⁻). These two products contain chlorine in different oxidation states.

✔ Chlorine is reduced to

Cl⁻

✔ Chlorine is oxidised to

ClO⁻

This is exactly what examiners mean by

disproportionation.

🧪 Key reaction (cold alkali):

Cl₂ + 2OH⁻ →

Cl⁻ +

ClO⁻ + H₂O

🧼 This is the reaction used to make household bleach.

The chlorate(I) ion (ClO⁻) is the active ingredient responsible for the

disinfecting,

oxidising

and bleaching properties of bleach.

🔥 In hot, concentrated alkali, chlorine oxidises even further to the chlorate(V) ion (ClO₃⁻). This deeper oxidation sometimes appears in long-answer questions comparing cold vs hot conditions.

🧠 Top examiner tip: Any time chlorine forms both Cl⁻ and a chlorate species (HClO, ClO⁻, or ClO₃⁻), you should immediately identify the reaction as a disproportionation reaction.