Imagine the following scenario: A sealed flask contains a mixture of three gases; A, B and C involved in a reversible reaction. The system (the reacting substances) has reached equilibrium.

Now recall that at equilibrium the amounts of the three gases A, B and C present is constant, but the reaction has not stopped. It is just that the rates of the forward and reverse reactions are the same so it looks like the amounts of each gas present are constant but in reality the reaction between all three gases is still taking place.

What happens to the amounts of each gas in the flask if:

All of these questions can be answered using one simple idea- read on for more info...

Well to answer any of the questions from above we need to consider the work of the pioneering French chemist Henri Le Chatelier; whose work and research has enabled scientists to better understand how chemical equilibrium work under different conditions. His most famous contribution to this field is the principle that bears his name; Le Chatelier's Principle. This is a theory that helped chemists and other scientists understand how chemical systems (the reacting chemicals) at equilibrium respond to changes in reaction conditions, such as changes in temperature, pressure, or concentration. In essence Le Chatelier's Principle states that:

A chemical system at equilibrium will respond to a change in temperature, pressure or concentration by shifting in a way that minimises the effect of that change.

Here’s a simple way to picture what is meant by Le Chatelier's Principle and a system “opposing” a change. It is only an analogy but it can be surprisingly helpful.

Imagine a frustrated mum trying to get her sleepy son out of bed in the morning to ensure he is not late for school again. Now the key to understanding this analogy is that every time the annoyed mum does something to encourage her lazy son to get up and out of bed, he reacts by doing the opposite; for example

A chemical system at equilibrium behaves in a similar way to the boy wanting to stay in his nice warm bed. When a change is applied the system (the reacting chemicals) responds by trying to reduce the effect of that change.

In chemistry the “annoyed mum ” is the change you apply (temperature, pressure or concentration) and the “lazy boy” is the system at equilibrium adjusting itself in response to the change.

Key terms 🔑

🌊 Equilibrium

The point in a reversible reaction where the forward and reverse reactions occur at the same rate.

🔁 Reversible reaction

A reaction in which reactants can form products and products can reform reactants.

🔥 Exothermic

A reaction that releases heat energy to the surroundings.

❄️ Endothermic

A reaction that absorbs heat energy from the surroundings.

⚗️ System

The reacting chemicals being studied.

🌍 Surroundings

Everything outside the system, including the container and the environment.

📍 Position of equilibrium

The relative amounts of reactants and products present at equilibrium.

⚡ Catalyst

A substance that increases the rate of a reaction without changing the position of equilibrium.

A useful way to think about equilibrium is that it is a stable point for any system under a given set of conditions. If you change the conditions (for example, heat the system or change the pressure or change the concentration of any of the reactants or products then the system will re-adjust and settle at a new equilibrium position.

At this new position the amounts of reactants and products may be different but the rate of the forward and reverse reactions will again be equal.

Let us look at any example of how to use Le Chatelier's principle to explain how pressure changes the position of equilibrium in a reversible reaction. However you should be aware that pressure changes only applies to reactions involving gases. Solids and liquids are not significantly affected by changes in pressure.

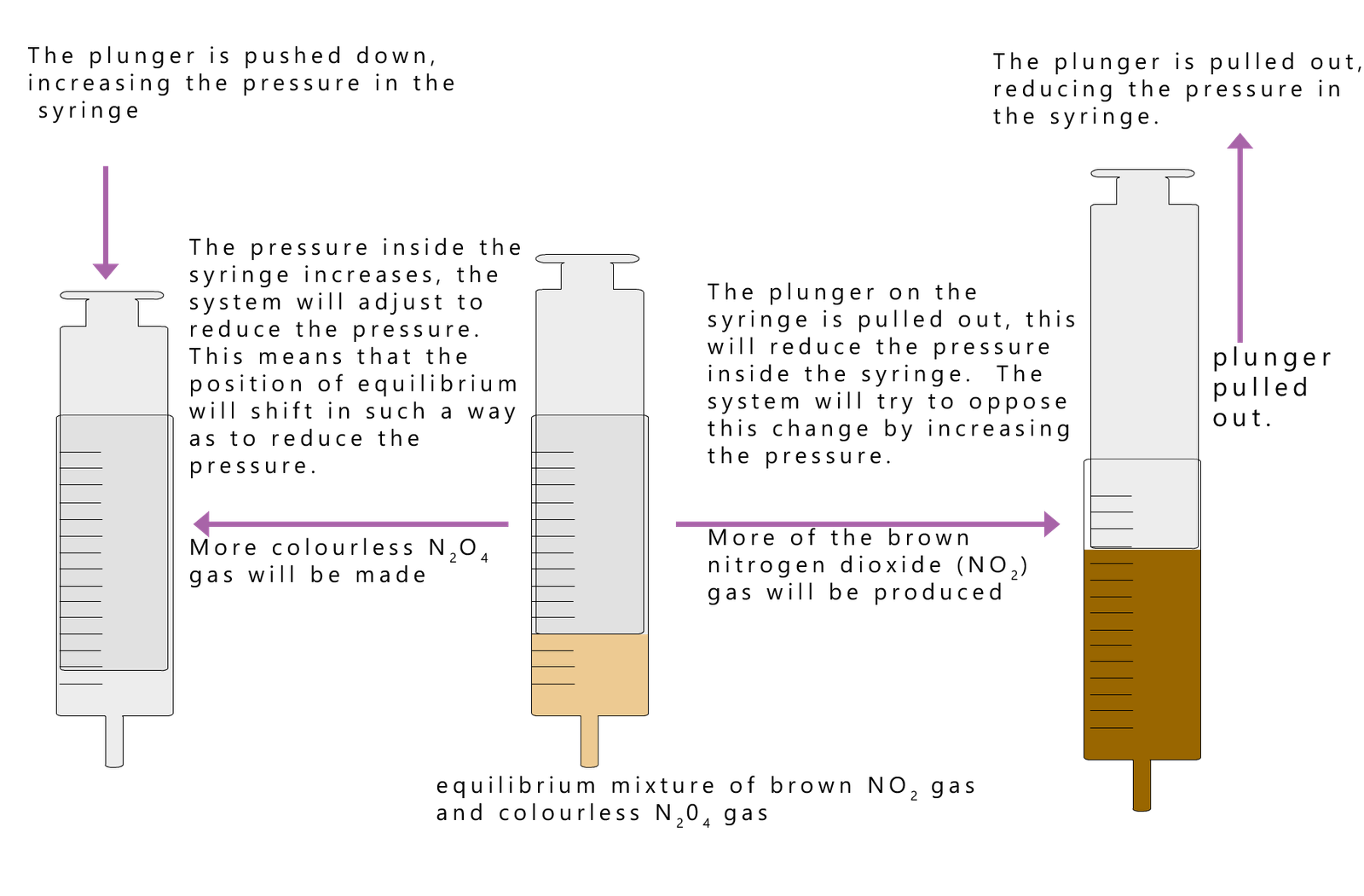

Consider the reversible reaction between the colourless gas nitrogen tetroxide (N2O4) and the brown gas nitrogen dioxide (NO2). Now dinitrogen tetraoxide (N2O4) is colourless toxic gas with a very unpleasant smell. Despite the fact that it is a colourless gas it appears reddy brown at room temperature and pressure since it exists in an equilibrium mixture with brown nitrogen dioxide gas, as shown in the equations below:

We can see from the balanced symbolic equation that one mole of N2O4 will decompose to form two moles of NO2. Now the side of the equation with the least number of moles of gas can be regarded as the low pressure side and the side of the equation with the most moles of gas can be regarded as the high pressure side of the equilibrium mixture. So in our equation the side with the dinitrogen tetraoxide will be the low pressure side and the side of the equation containing the nitrogen dioxide gas can be regarded as the high pressure side.

So what will happen to this reversible reaction at equilibrium if the pressure is changed? Well according to Le Chatelier's Principle a system at equilibrium will adjust the position of equilibrium in such a way to minimise or oppose the change applied to it, so we can say that:

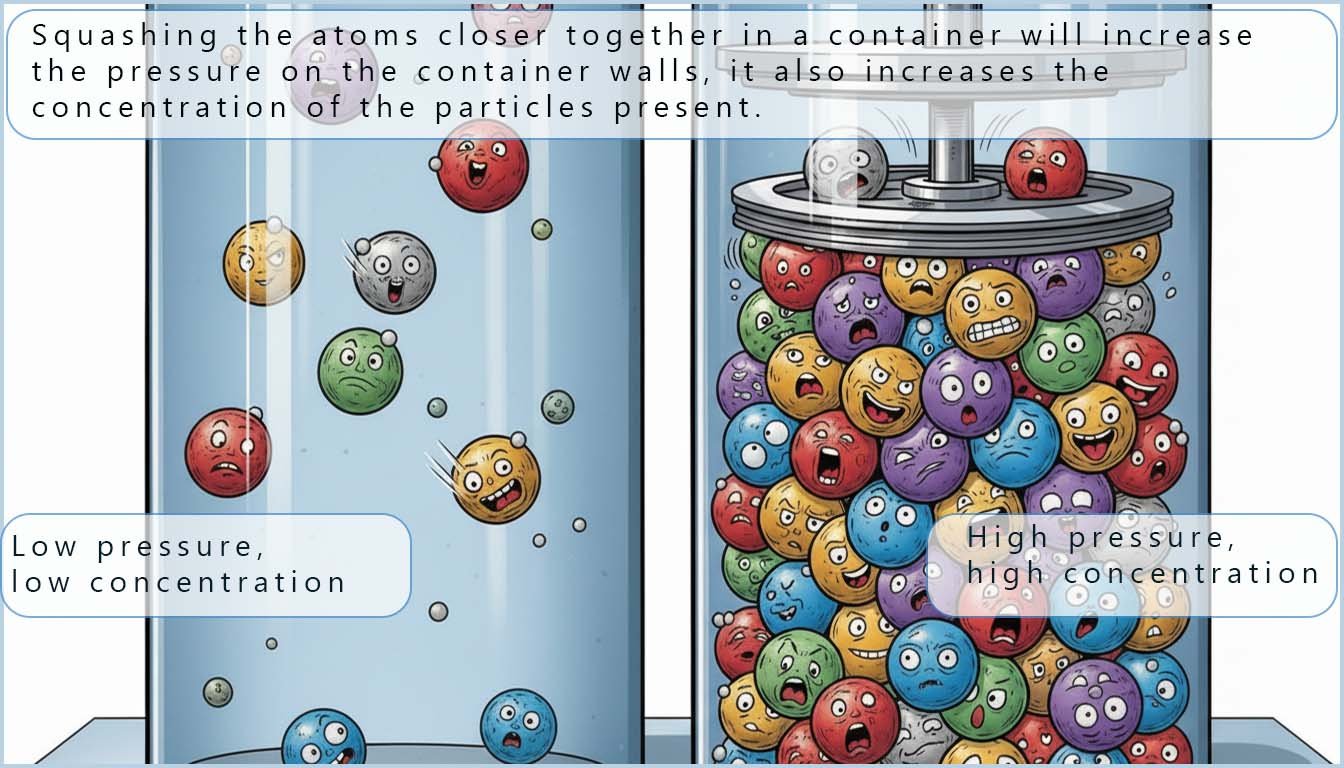

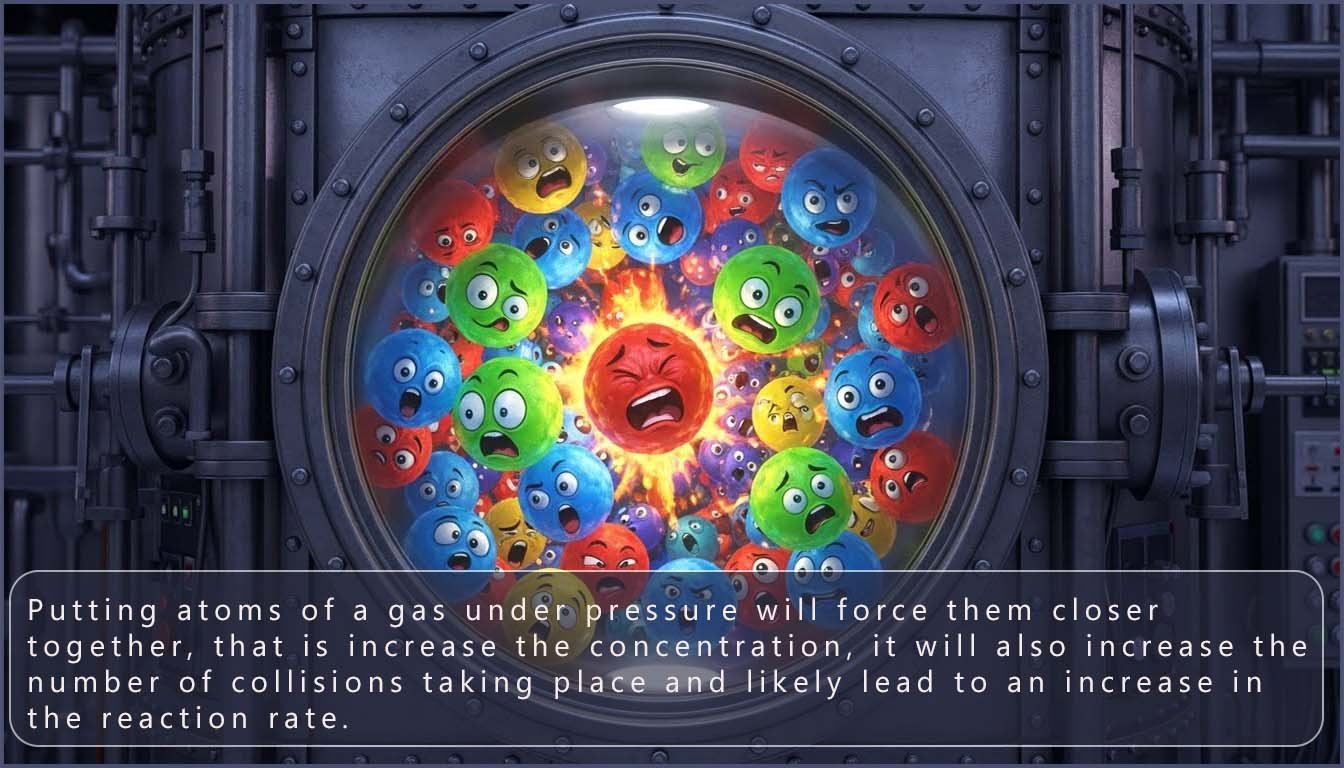

Gases inside a container exert a pressure on the container walls by colliding with them.

The more frequent and more forceful these collisions are the greater the pressure exerted by the gas particles on the container walls.

When dealing with gases changing the pressure also changes how closely packed the gas particles are. This has a similar effect to changing the concentration of the gases in the system.

For example, if the gas particles in a container are forced closer together (by reducing the volume), both the pressure and the concentration of the gas particles increase because there are more particles per unit volume.

Increasing pressure (by decreasing volume) increases the number of gas particles per unit volume. In this way increasing pressure has a similar effect to increasing concentration for gases.

At room temperature an equilibrium mixture of brown nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and the colourless gas dinitrogen tetraoxide (N2O4) typically appears as a light to medium brown gas, this simply because the dark brown colour of the nitrogen dioxide gas is diluted by the colourless dinitrogen tetraoxide. We can use Le Chatelier's Principle to work out what will happen to this equilibrium mixture when it is heated and also cooled and the changing colour of the equilibrium mixture should give a big clue as to what is actually happening. Before we look in detail at how temperature affects this equilibrium mixture take a minute or so to study the image below and try to work out what is happening yourself.

So how can we use Le Chatelier's Principle to explain what happens when a flask containing this equilibrium mixture of gases is heated and cooled? Well...

We can summarise this by saying:

🔥 Heating favours the endothermic direction;

❄️ Cooling favours the exothermic direction.

Hopefully by now you are beginning to become an expert on Le Chatelier's Principle and are now able to predict how it will affect reacting systems at equilibrium. Let us consider a different reaction to investigate and predict how Le Chatelier's Principle can be used to predict the changes that occur in a reacting system at equilibrium when we change the concentration of one or more of the reactants or products.

Let us briefly consider a reaction that you will likely meet again during your A-level chemistry course, the reaction between iron(III) ions (Fe3+(aq)) and thiocyanate ions (SCN−(aq)). Solutions containing Fe3+(aq) ions are pale yellow in colour while a solution of potassium thiocyanate is colourless. However if even a small amount of thiocyanate ions (SCN−(aq)) are added to a solution containing Fe3+(aq) ions an intense blood-red coloured solution forms. In fact, this reaction is so sensitive that it can be used as a test for the presence of Fe3+(aq) ions in solution.

Below is an image to show the colour changes taking place during this reaction along with a simplifed equation for the reaction:

.jpg)

Now it's your turn to make some predictions using Le Chatelier's Principle for the reaction at equilibrium below:

Predict what will happen to the intensity of the red colour in each case below, then click to reveal the explanation.

The last factor to consider is how we can use Le Chatelier's Principle to explain the effects of a catalyst on a reaction at equilibrium:

Consider a system at equilibrium:

Prediction: What happens to the amounts of A, B and C at equilibrium if a catalyst is added?

A catalyst increases the rate of both the forward and reverse reactions. This means the system reaches equilibrium faster, but the position of equilibrium does not change. The final amounts of A, B and C at equilibrium stay the same.

You probably already know that catalysts speed up a reaction by:

However:

So a catalyst will get the reacting system to equilibrium faster but it will NOT alter the amounts of the reactants or products at equilibrium.

The table below summarises the effects on the position of equilibrium of changing the temperature, pressure, concentration or adding a catalyst to a reacting system at equilibrium.

| Change made | Effect on position of equilibrium | Why (Le Chatelier) |

|---|---|---|

| Increase temperature | Shifts in the endothermic direction | System absorbs added heat |

| Decrease temperature | Shifts in the exothermic direction | System releases heat |

| Increase pressure (gases only) |

Shifts towards fewer moles of gas | System reduces pressure |

| Decrease pressure (gases only) |

Shifts towards more moles of gas | System increases pressure |

| Increase concentration | Shifts to reduce that substance | System opposes added particles |

| Decrease concentration | Shifts to replace that substance | System replaces what was removed |

| Add a catalyst | No change in position | Forward and reverse rates increase equally |