Chemistry only

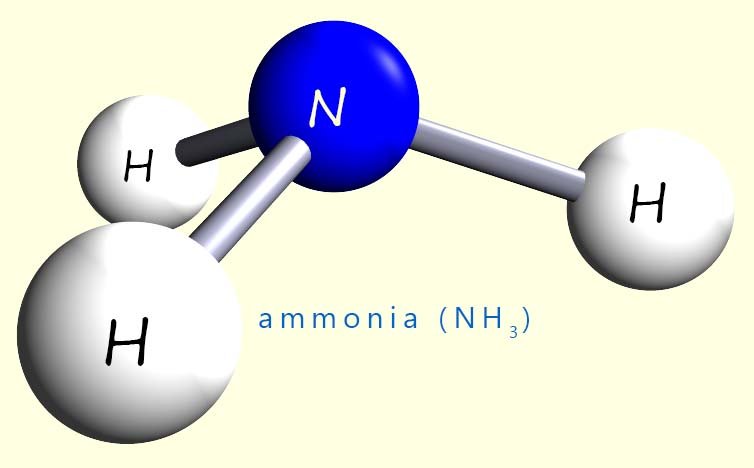

Fritz Haber (1868-1934) and Carl Bosch (1874-1940) developed a process to synthesis the gas ammonia. Now ammonia is a colourless gas with a choking and distinctive smell which makes it immediately recognizable. It is a simple molecule made up of only one nitrogen atom and three hydrogen atoms; its molecular formula is NH3.

Ammonia is a very important gas simply because it is needed to manufacture fertilisers. The availability of synthetic fertilisers made it possible to increase soil fertility which in turn lead to an increase in crop yields and dramatically increased the amount of food available in the global food market. For their work in the synthesis of ammonia both Haber and Bosch were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry. However at the time the decision to award Haber the Nobel Prize in chemistry was not without controversy.

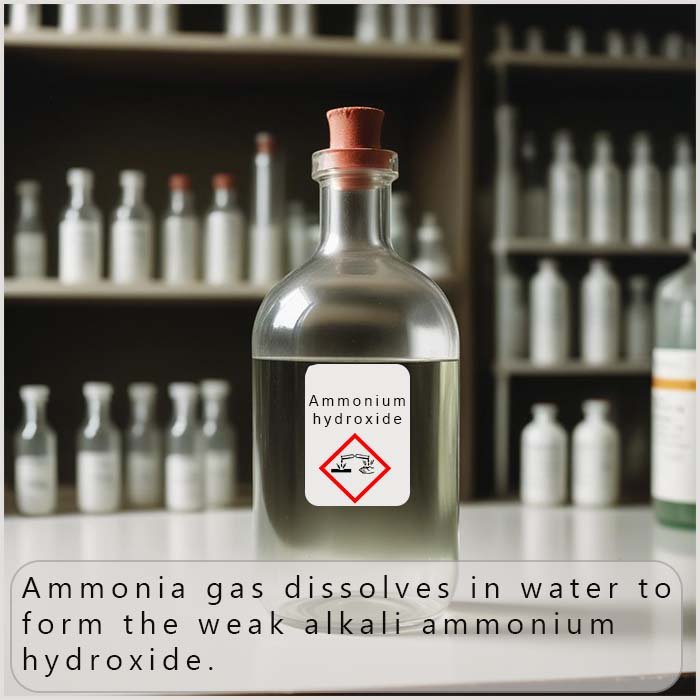

Ammonia is an excellent base, it is very very soluble in water where it dissolves to form the weak alkali ammonium hydroxide:

The second equation above might be better written as shown below since ammonium hydroxide is a weak alkali and it dissolves in water to form ammonium ions (NH4+) and hydroxide ions (OH-(aq))

Ammonia gas is easy to liquefy, this is done by simply compressing gaseous ammonia or by cooling it down to -330C (its boiling point). Ammonia is manufactured on a large scale in the UK using the method developed by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch. The main use of ammonia is in the manufacture of fertilisers, indeed a significant portion of the world's food production depends on the use of fertilisers produced by the Haber-Bosch process. Ammonia is also used in the manufacture of explosives, for example ammonia is used in the production of ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), which is a widely used ingredient in certain types of explosives.

In industry ammonia is made on a large scale using the process devised by the German chemist Fritz Haber in 1909. Being a small and simple molecule it may appear at first glance that making ammonia (NH3) would be straightforward, simply react nitrogen gas (N2) and hydrogen gas (H2) together to make ammonia (NH3). However there are a number of problems that need to be overcome before large amounts of ammonia can be made.

1. Large amounts of hydrogen gas will be needed. The hydrogen used in the Haber-Bosch process is obtained by reacting methane (CH4) or natural gas with steam using a nickel catalyst. This reaction is often referred to as steam-reforming, equations for this reaction are shown below:

The carbon monoxide produced above can be reacted further with steam to yield more hydrogen.

2. The nitrogen gas needed to make ammonia is obtained from the air. Air is approximately 78% nitrogen. All that is required is to remove the other gases, mainly oxygen, carbon dioxide and water vapour which would be considered impurities and this will leave the nitrogen gas.

3. The equation for the Haber process used to make ammonia is shown below.

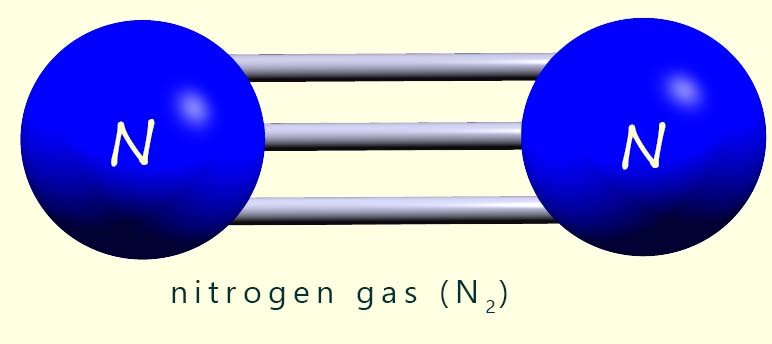

Perhaps the first point to note from this equation is that the reaction is reversible. Under normal lab conditions

nitrogen and hydrogen

will react to produce an equilibrium mixture which contains very little ammonia. The

main reason for this is the fact that nitrogen

is a particularly unreactive gas. Each nitrogen molecule is held together by a triple covalent bond (shown opposite) which requires a large amount

of energy to break. This triple covalent bond results in a

very high activation energy for the reaction and so under lab conditions

there is not enough energy to break many of these triple covalent bonds so the

forward reaction is very slow.

Perhaps the first point to note from this equation is that the reaction is reversible. Under normal lab conditions

nitrogen and hydrogen

will react to produce an equilibrium mixture which contains very little ammonia. The

main reason for this is the fact that nitrogen

is a particularly unreactive gas. Each nitrogen molecule is held together by a triple covalent bond (shown opposite) which requires a large amount

of energy to break. This triple covalent bond results in a

very high activation energy for the reaction and so under lab conditions

there is not enough energy to break many of these triple covalent bonds so the

forward reaction is very slow.

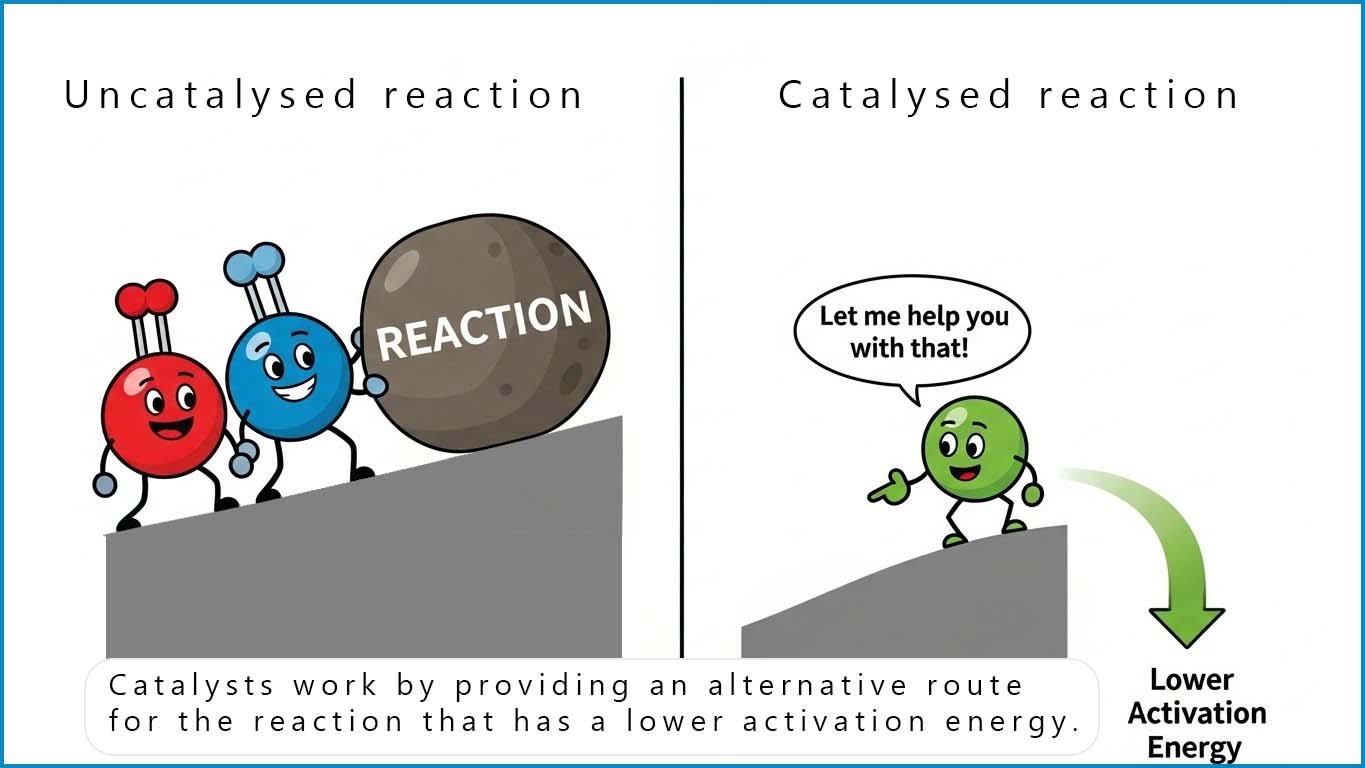

The Haber process uses a catalyst to help lower the activation energy and reduce the amount of energy needed to break the triple covalent bond in the nitrogen molecules and get the reaction going at a reasonable rate. However in order to have any ammonia to sell and make a profit there are a number of other factors you need to think about before setting up a chemical plant to manufacture ammonia.

As a manager of a chemical plant producing ammonia there are a number of

factors you need to think about in order to produce a

reasonable amount of ammonia to sell for a profit at the end of the day.

Consider the reversible reaction for the formation of ammonia given below:

As a manager of a chemical plant producing ammonia there are a number of

factors you need to think about in order to produce a

reasonable amount of ammonia to sell for a profit at the end of the day.

Consider the reversible reaction for the formation of ammonia given below:

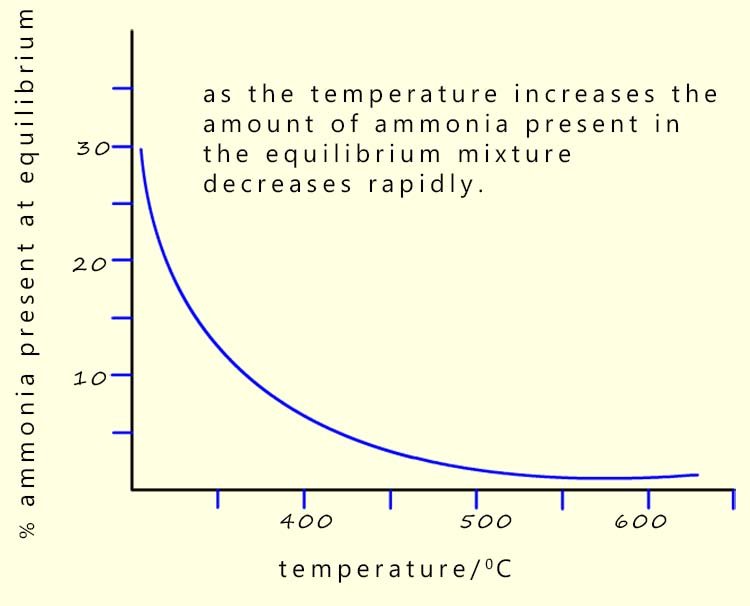

The forward reaction is exothermic, so according to Le Chatelier's principle lowering the temperature will cause the position of equilibrium to shift to the right and more ammonia will be produced (see graph opposite). The problem is that lowering the temperature will also cause the rate of reaction to slow down. So while lowering the temperature will push the position of equilibrium to the right it may take weeks or even years to happen.

Also to work efficiently the catalyst used in the Haber process needs a temperature of between 400-500°C🔥. So a low temperature is not really an option if you want to produce ammonia quickly. However a high temperature is not an option either, since according to Le Chatelier's principle an increase in temperature will force the position of equilibrium to the left, that is reduce the amount of product, so less ammonia.

The answer to this temperature issue is to use a compromise temperature. That is a temperature that will produce a reasonable yield of ammonia in a reasonable time. A temperature of around 450°C🔥 is usually used in the Haber process as a compromise temperature. The graph opposite shows that as the temperature increases the amount of ammonia present in the equilibrium mixture decreases.

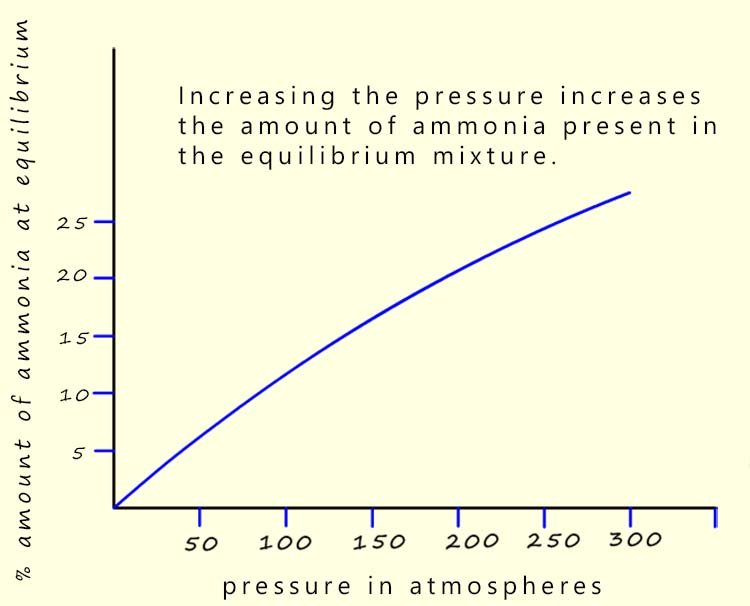

However even with the use of a compromise temperature most of the nitrogen and hydrogen are still unreacted and little ammonia is actually produced. So what else can be done to try and increase the amount of ammonia in the equilibrium mixture? Well if you look at the equation for the Haber process you will see that there are 4 moles of gas on the reactants side and only 2 moles of gas on the product side of the equation:

So again using Le Chatelier's principle we can alter the amount of reactants and products in the equilibrium mixture by

changing the pressure. If we increase the pressure

then the system (the reacting chemicals) will respond according to Le Chatelier's principle by attempting to

lower the pressure, this can be done by forcing the

position of equilibrium to the side of the equation with the least

number of moles of gas present, that is the product side.

So we can say that the higher the pressure the more

ammonia will be present

in the equilibrium mixture.

So again using Le Chatelier's principle we can alter the amount of reactants and products in the equilibrium mixture by

changing the pressure. If we increase the pressure

then the system (the reacting chemicals) will respond according to Le Chatelier's principle by attempting to

lower the pressure, this can be done by forcing the

position of equilibrium to the side of the equation with the least

number of moles of gas present, that is the product side.

So we can say that the higher the pressure the more

ammonia will be present

in the equilibrium mixture.

However high pressure brings its own problems, t will be very expensive to build pipes, valves and reactors that can withstand and maintain high pressures not to mention the cost of the compressors needed to maintain these high pressures. High pressure also brings an increased risk of explosion.

So as with temperature a balance needs to be struck here. There is not point or profit to be gained operating a chemical plant at very high pressures due to the expense and danger resulting from these pressures, so a compromise pressure of around 200-250 atmospheres is normally used in the Haber process. This is a balance between economics, safety and need to make a reasonable amount of ammonia.

A catalyst is used in the Haber process to speed up the reaction. Recall that catalysts speed up chemical reactions by providing an alternative route to the products but crucially this route has a lower activation energy. A catalyst will have no effect on the position of equilibrium or alter the amounts of reactant or product present at equilibrium, the catalyst will however speed up the reaction rate considerably. The catalyst used in the Haber process is an activated iron catalyst. It works most efficiently around 400°C🔥

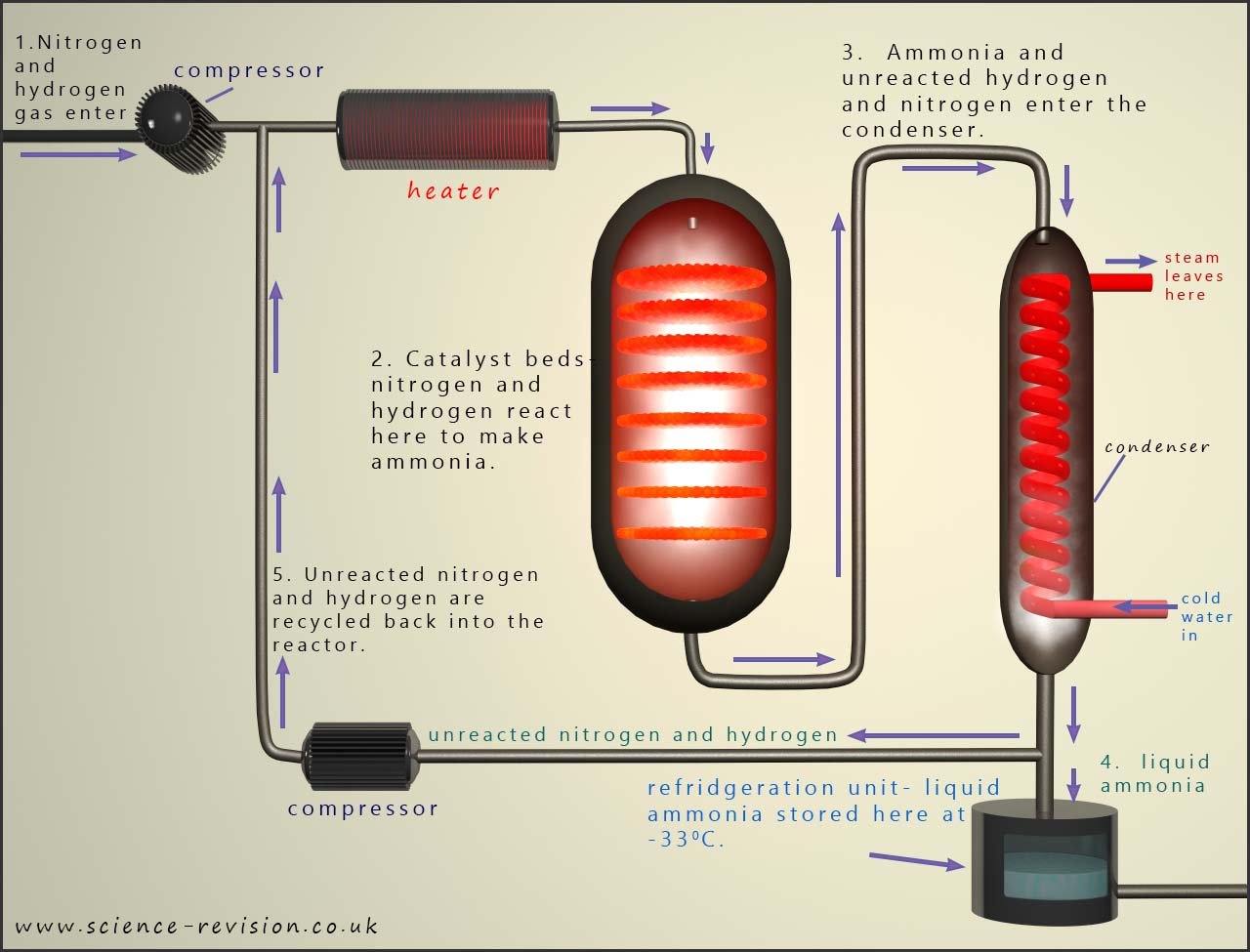

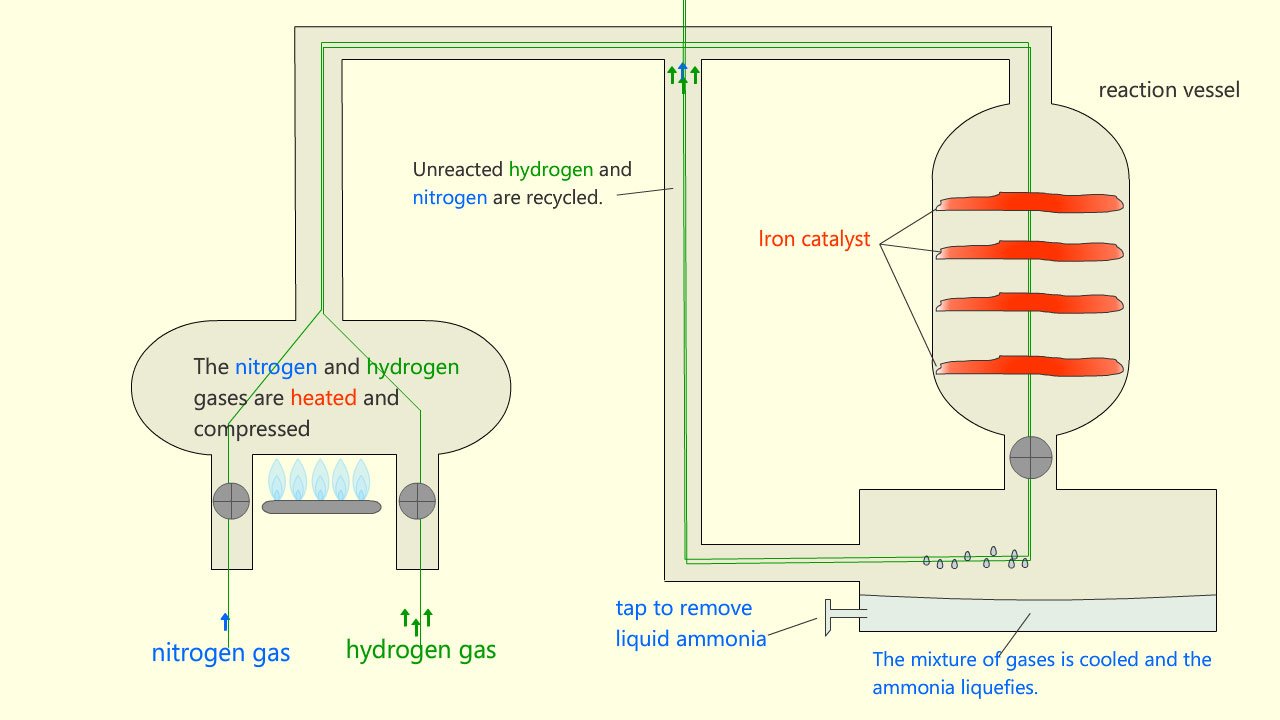

A simplified outline of the Haber process is shown in the image below:

The nitrogen and hydrogen are mixed in the ratio of 1:3 (1 part nitrogen to 3 parts hydrogen), just as in the equation for the Haber process. These gases are then compressed to as high a pressure as is economically viable for the plant, normally around 200 atmospheres. The mixture of gases are then pre-heated before they enter the reactor at around 4500C. On the surface of the iron catalyst the gases react and around 15% yield of ammonia is produced, however about 85% of the nitrogen and hydrogen gases are unreacted.

Once the mixture of gases leave the reactor they enter a condenser (cooler). At this point there is a mixture of ammonia and unreacted nitrogen and hydrogen. The ammonia present will easily liquefy under pressure after leaving the cooler. It will then be stored in a separate refrigeration vessel. The unreacted nitrogen and hydrogen gases are then recycled back through the reactor again. With continual recycling of the nitrogen and hydrogen up to 98% of it can be turned into ammonia. The diagram below shows a schematic representation of how the ammonia is produced in the Haber-Bosch process.

Read the articles below, they detail a darker side to Fritz Haber's nature and how his reluctance to support his brilliant and talent wife pursue her chemistry career and his insistence on developing poison gases during World War One lead to tragedy.

This enrichment section looks at the people behind the Haber process. It explores how Fritz Haber’s chemistry helped feed the world but was also used in the first large-scale poison gas attacks, and how his wife, the chemist Clara Immerwahr, protested against this misuse of science.

Fritz Haber was born in 1868 in Breslau, in what is now Poland. He became a leading industrial chemist at a time when scientists were desperately searching for a way to turn the nitrogen in the air into fertiliser. Natural sources of nitrate were running out, and many people feared that future famines would follow.

Haber’s breakthrough was to find conditions where nitrogen and hydrogen would react together to form ammonia. Working at high pressures and high temperatures, and using an iron catalyst, he developed a process that later became known as the Haber–Bosch process. Once this process was scaled up in factories, it allowed huge quantities of ammonia to be made for fertilisers.

Synthetic fertilisers transformed farming. Crop yields increased dramatically and food production rose around the world. Historians often say that without the Haber–Bosch process the Earth could not support its present population.

However, even during his lifetime, some people noticed a troubling contradiction. How could the same chemist whose work helped to feed millions also be linked to some of the most harmful uses of chemistry in war?

Clara Immerwahr was born in 1870, also near Breslau. From an early age she showed a strong talent for science, but at that time girls were not expected to become professional chemists. Clara persevered anyway and, in 1900, became the first woman in Germany to earn a PhD in chemistry.

She worked with the respected chemist Richard Abegg, published research and gave lectures for women’s groups. Her success should have been the start of a long scientific career.

Instead, when she married Fritz Haber in 1901, social expectations closed many doors. Women were not allowed to hold university posts, and even unpaid laboratory work for married women was discouraged. Clara found herself expected to run the household and support Fritz’s ambitions, rather than pursue her own scientific ideas.

Letters and later accounts suggest that Clara felt increasingly frustrated and isolated. Her story reminds us how many talented people, especially women, were pushed out of science by unfair rules and attitudes.

When the First World War began in 1914, Fritz Haber believed that chemistry could help Germany win the conflict. He argued that if a powerful new weapon could break the stalemate of trench warfare, the war might end more quickly.

At the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute he led teams of chemists who developed and tested different poisonous gases. This work led to the first large-scale use of chlorine gas on the Western Front, at the Battle of Ypres in April 1915. Clouds of gas drifted over the trenches and thousands of soldiers were injured or killed.

Reports of the attack shocked people all over the world. Gas attacks continued on all sides during the war, and they are now remembered as one of the most disturbing aspects of World War I.

This part of Haber’s life is often described as the “dark side” of his legacy. The same skills that had helped to create life-saving fertilisers were now being used to design more effective weapons.

Clara was horrified by her husband’s work on chemical weapons. She believed strongly that science should be used to improve life, not to create new ways of causing suffering. She reportedly described the use of chlorine gas as a misuse of science and a betrayal of the values she had devoted her own studies to.

Clara had already sacrificed much of her own scientific career. Now she was being asked to watch while the chemistry she loved was turned into a weapon, while Fritz was praised for his role in the gas attacks. This made the conflict between her conscience and his ambitions even harder to bear.

Shortly after the first gas attack at Ypres in 1915, Clara took her own life. Many historians see this as a tragic final protest against the direction in which science was being pushed.

Clara’s story raises important questions for today. Who is responsible for how scientific ideas are used – the scientists, governments, or society as a whole? Should scientists refuse to work on projects they believe are wrong, even if their country is at war?

Alter the temperature and pressure in the activity below to see how this affects the yield of ammonia. Try for example keeping the temperature constant and then alter the pressure to find out what happens to the yield of ammonia, though you should realise that the yield of ammonia is not the only variable to consider when deciding on the reaction conditions.

Choose the conditions for your ammonia plant. Try to balance rate, yield and cost/safety. Then hit “Run plant” and see how well your choices perform.

Yield of ammonia: –

Rate of reaction: –

Cost and safety: –

Before you try the practice quick quiz or the questions on The Haber Process below check out the following misconceptions that many students have regarding this process:

Each statement appears plausible — but each hides a common misconception. Click to reveal the correct chemistry.

The forward reaction is exothermic. Higher temperature pushes equilibrium backwards and reduces the yield. Industry uses a compromise temperature (≈450°C) to balance yield and rate.

A catalyst does not change yield. It only speeds up the rate at which equilibrium is reached. It speeds up both forward and reverse reactions equally.

High pressure does increase yield because fewer gas molecules are produced, but it is hugely expensive and unsafe to run extremely high pressures. Industry uses a compromise ~200 atm.

Only about 15% converts per pass. The unreacted nitrogen and hydrogen are recycled repeatedly until most eventually forms ammonia.

The catalyst slowly becomes poisoned by impurities such as carbon monoxide. This reduces efficiency and it must be replaced periodically.