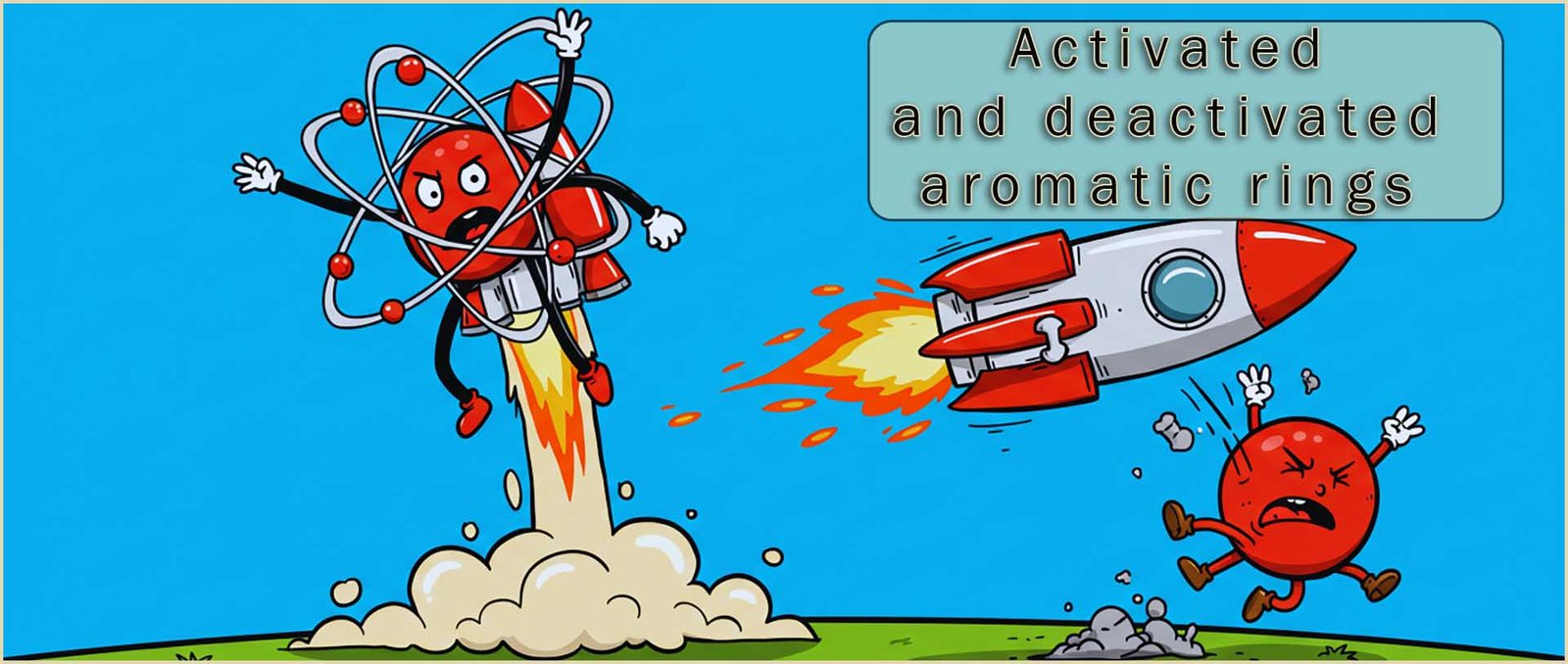

As you already know aromatic rings undergoes electrophilic substitution reactions; here one of the hydrogen atoms in the aromatic ring is replaced by another substituent to form a monosubstituted aromatic ring. The mechanism for this reaction is shown below using the Kekulé structure for benzene as an example:

In this reaction the delocalised pi(π) electrons in the aromatic ring attack an electrophile and generate a resonance stabilised intermediate cyclohexadienyl carbocation; which then quickly loses a hydrogen ion (H+) to regenerate the delocalised pi(π) electron system in the aromatic ring.

On this page we will look at what happens when we try to add another substituent to a monosubstituted aromatic ring to form a disubstituted aromatic ring and discuss how any added substituent affects the overall reactivity of an aromatic ring.

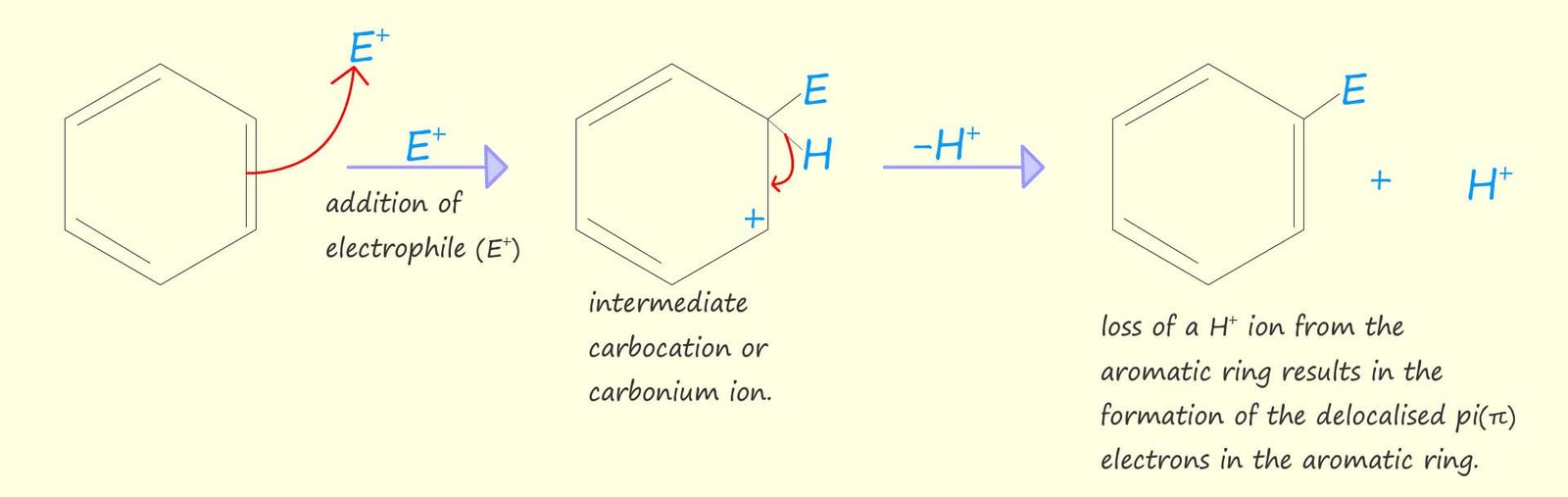

Substituents already attached to an aromatic ring can affect how readily it is able to undergo further electrophilic substitution reactions, for example consider the case shown in the image below. Here a substituent (X) has been added to an aromatic ring, now if substituent (X) is able to push electron density into the aromatic ring then this will obviously increase the electron density in the aromatic ring and increase its ability to act as a nucleophile and attack an electrophile. In this case we would say that substituent (X) has activated the aromatic ring to undergo further electrophilic substitution reactions.

However in the second example below substituent (Y) is an electron withdrawing group which will reduce the electron density in the aromatic ring; this means that the aromatic ring will be less able to attack an electrophile and take part in further electrophilic substitution reactions. In this case we would say that substituent (Y) has deactivated the aromatic ring and it is less likely to undergo further electrophilic substitution reactions.

There is essentially two ways in which a substituent attached to an aromatic ring can add or withdraw electron density from the aromatic ring; that is activate or deactivate the aromatic ring. The two ways are:

There is essentially two ways in which a substituent attached to an aromatic ring can add or withdraw electron density from the aromatic ring; that is activate or deactivate the aromatic ring. The two ways are:

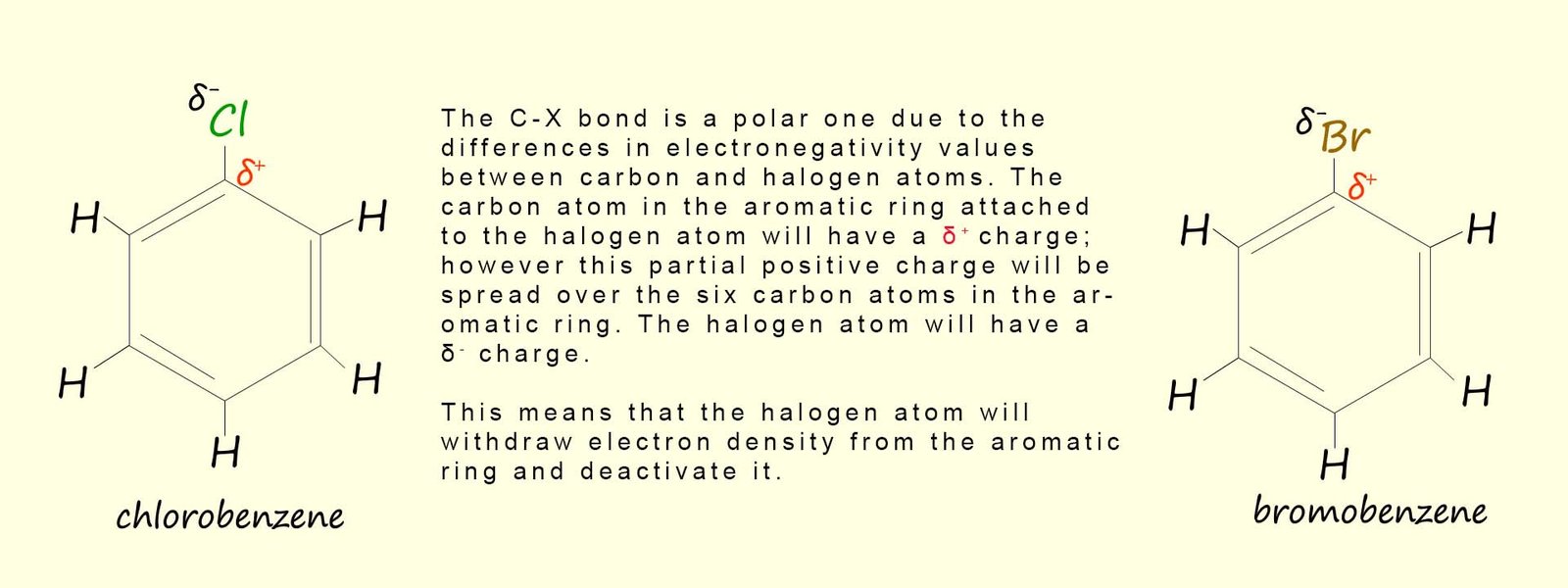

Let's start by looking at inductive effects and how they affect the reactivity of aromatic rings. One obvious way to change the electron density in an aromatic ring is to attach an atom with a large electronegativity value to it; for example consider the two molecules shown in the image below; these molecules are chlorobenzene and bromobenzene. Now halogen atoms such as F, Cl and Br have large electronegativity values and so the carbon-halogen bond (C-X bond) will be a polar one with the halogen atom having a δ- charge and the carbon atom in the aromatic ring attached to it will have a δ+ charge, this means that the halogen atoms will be withdrawing electron density from the aromatic ring through the C-X polar covalent bond, this reduction in electron density within the aromatic ring will deactivate it and make it less likely to undergo further electrophilic substitution reactions. However this effect is fairly mild and halogens are weak deactivators.

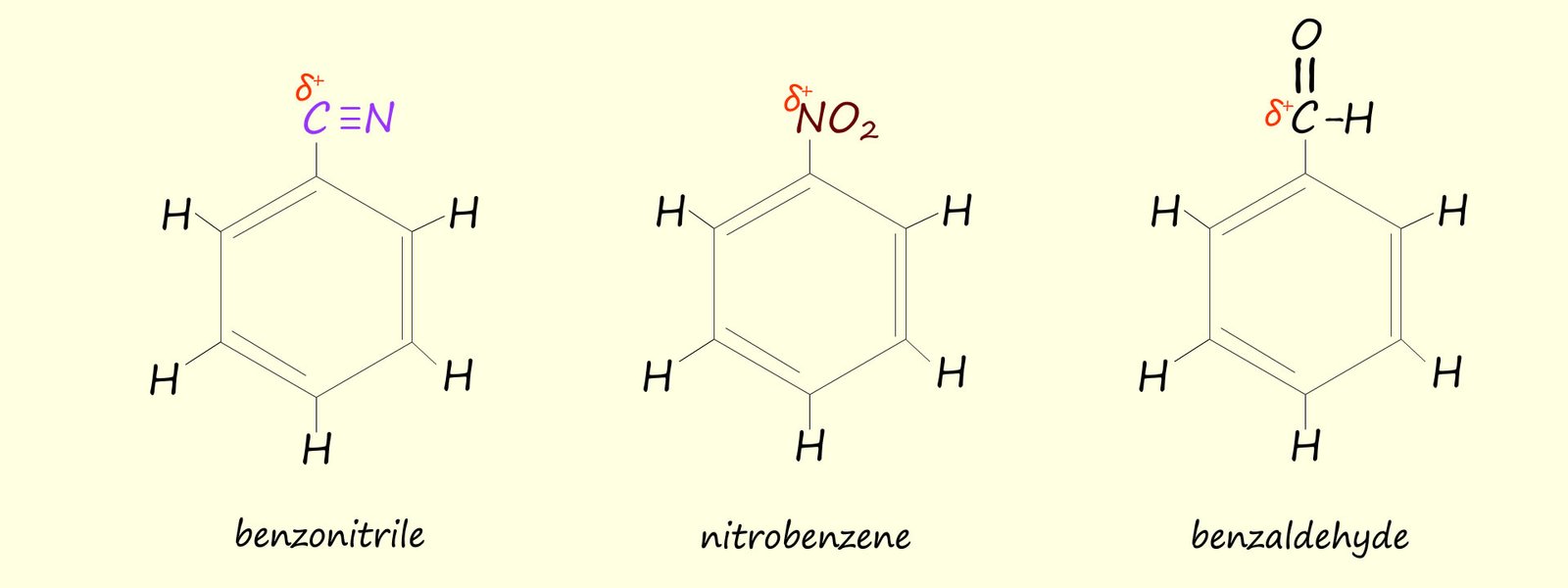

Some substituents such as the nitrile group (-CN), the nitro group (-NO2) and the carbonyl group (-CO) are all groups which contain dipoles, that is they contain atoms with polar covalent bond which have δ+ and δ- partial charges, if these groups are attached to an aromatic ring (see image below) then they will withdraw electron density from the aromatic ring and so deactivate it towards further electrophilic subsititution.

Alkyl groups such as methyl groups (-CH3), ethyl groups (-C2H5) and propyl groups (-C3H7) are able to activate aromatic rings, though very weakly; by pushing electron density into the aromatic ring. The C–C bonds in an alkyl group are slightly less electronegative than the aromatic ring’s sp2-hybridised carbon atoms. This causes a small positive inductive effect and electron density is pushed toward the aromatic ring through the carbon-carbon sigma bonds in the alkyl group.

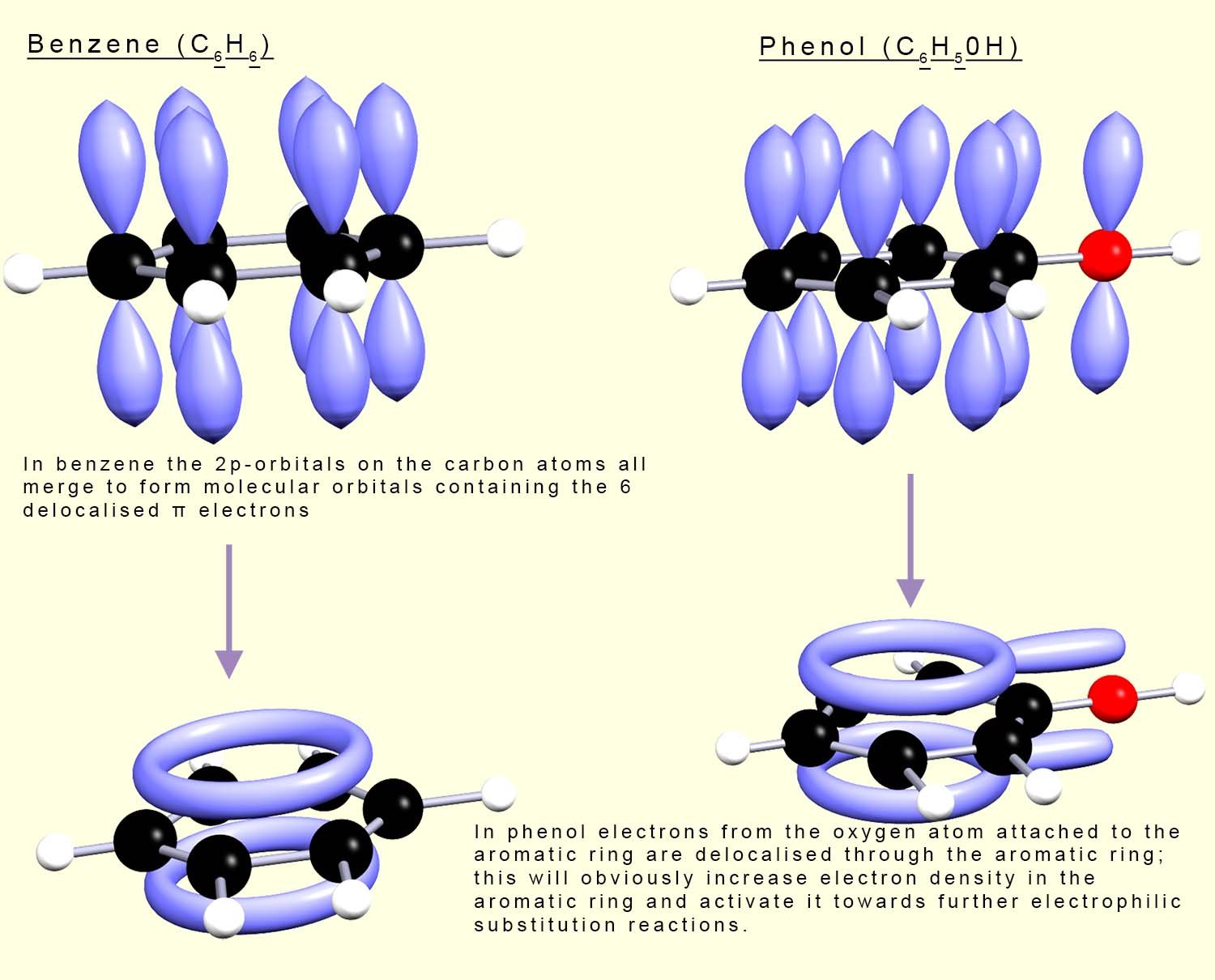

Groups such as the hydroxyl (-OH), nitro (-NO2) and carbonyl (-CO) which are attached to an aromatic ring all contain small atoms which have lone pairs of electrons in 2p-orbitals. Some of these electrons in these attached groups can merge with the 2p-orbitals in the aromatic ring and form an extended system of delocalised pi(π) electrons. Now in a benzene ring 2p-orbitals on each of the carbon atoms merge to form molecular orbitals which are situated above and below the plane of carbon atoms in the benzene ring and these orbitals contain the six delocalised pi(π) electrons found in the benzene ring; this is outlined in the image below. However any group attached to an aromatic ring can either feed in or remove electron density from the aromatic ring, that is activate or deactivate it.

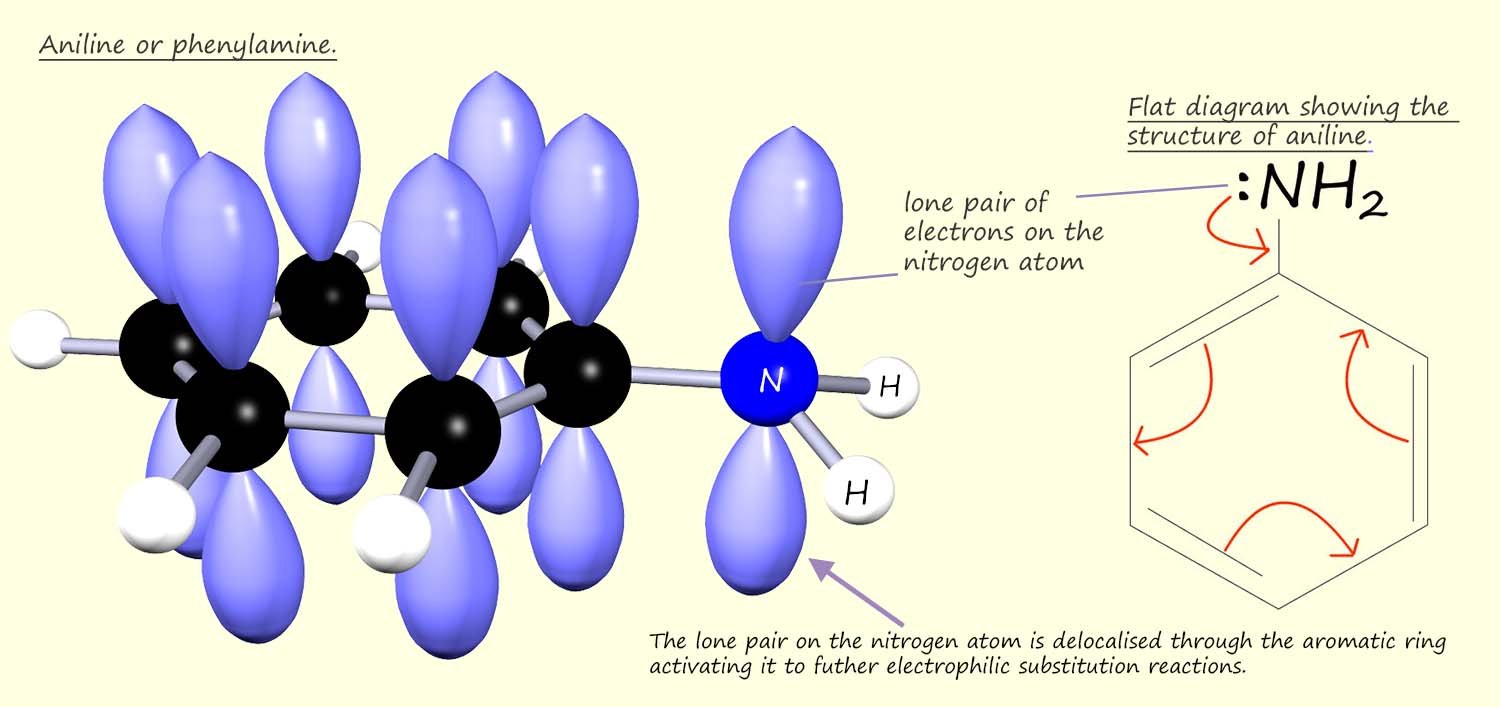

A similar result is found with the amino group (-NH2); which like the hydroxyl group in phenol contains a very electronegative nitrogen atom, but as with phenol the deactivating effect due to the presence of this nitrogen atom is over powered by the resonance effect when the nitrogen atom delocalises electrons through the aromatic ring. Aniline (C6H5NH2) like phenol; shown below contains an activated aromatic ring due to the delocalisation of electrons in the nitrogen atoms lone pair through the aromatic ring.

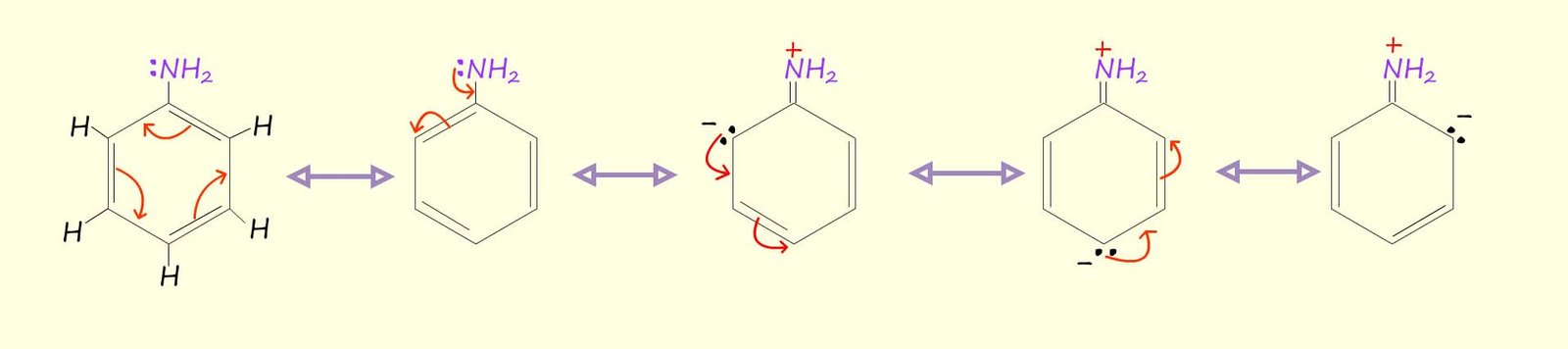

The diagram below shows how the amine group can push electron density into the aromatic ring and increase its electron density, you may notice that 3 out of 5 out of resonance structures have carry a lone pair of electrons; that is to say in 3 out of the five 5 resonance structures there is increased electron density at positions 2 and 4; this means that in practice any electrophile (electron deficient species) is likely to add to positions 2 and 4 in any further electrophilic substitution reactions that this activated aromatic ring undergoes. Positions 2 and 4 are often referred to as the ortho and para positions.

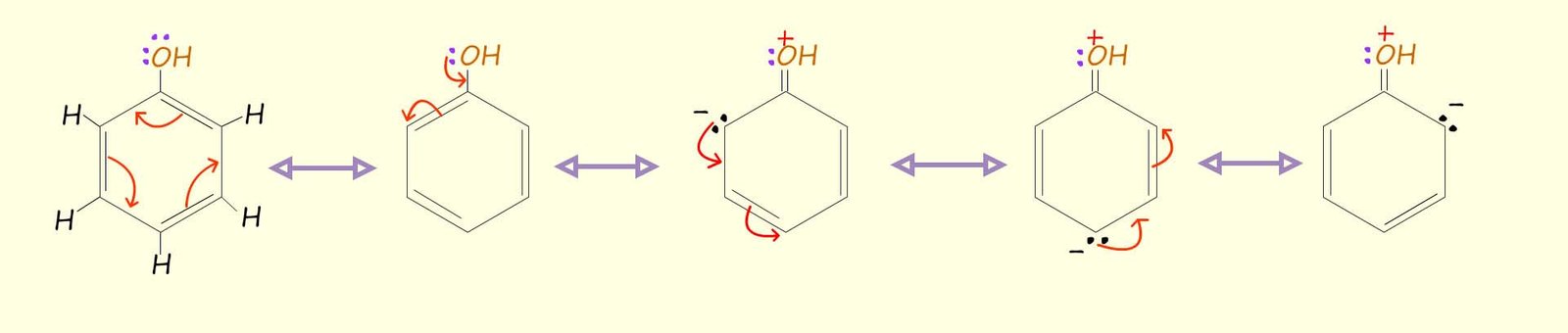

It is possible to draw an almost identical set of structures to show the resonance hybrid structures for phenol, all that is required is to swap the amino group (-NH2) in aniline for a hydroxyl group (-OH):

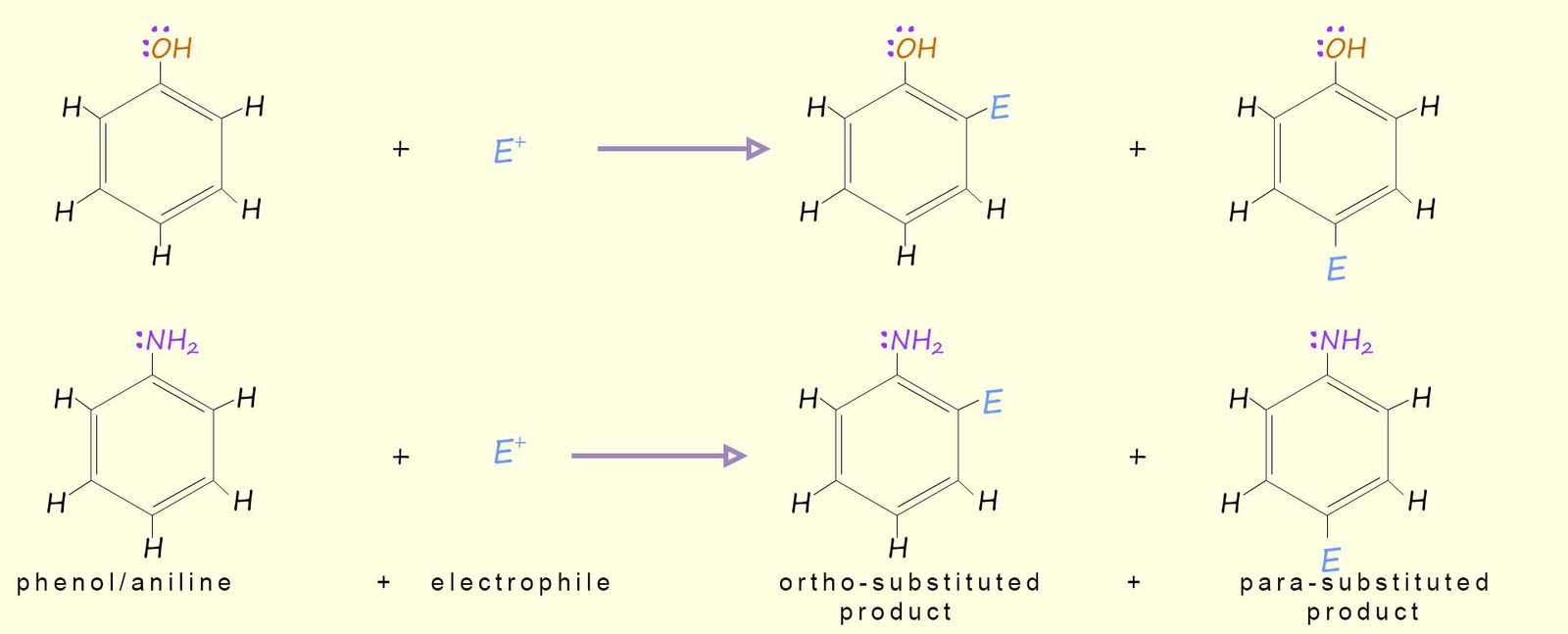

And when each of these two substances reacts with an electrophile (E+) the major products will be:

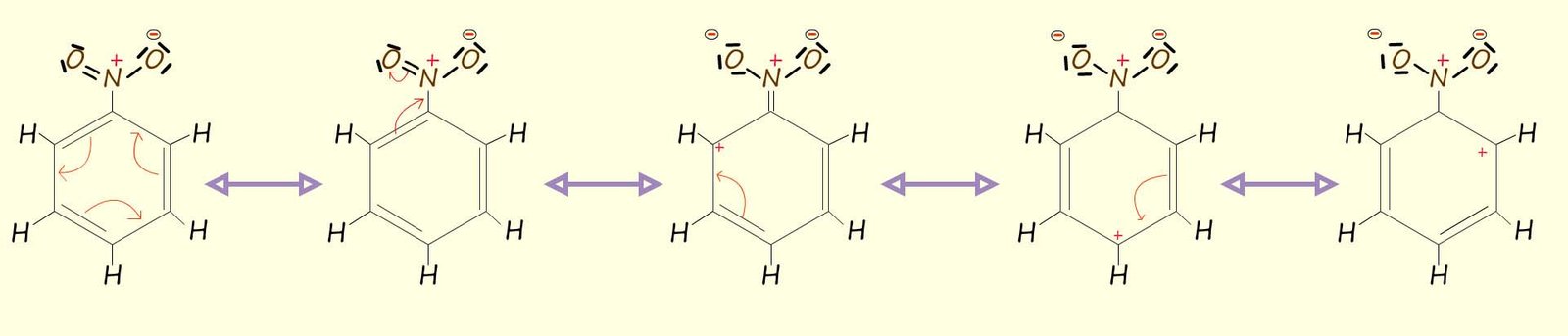

However not all attached substituents will donate electrons by resonance into the aromatic ring. The nitro group (NO2) and the carbonyl group (-CO) are two groups that will strongly deactivate the aromatic ring by withdrawing the electron density from it, for example the diagram below shows resonance hybrid structures for nitrobenzene; here you can clearly see that as the nitro group withdraws electron density from the aromatic ring it will deactivate all positions in the aromatic ring from any further electrophilic substitution reactions. However if you study the images carefully you will notice that in 3 out of the 5 resonance hybrid strutures positions 2 and 4 carry a positive charge; that is the ortho and para positions, so we can say that the nitro group (-NO2) deactivates al positions in the aromatic ring but that positions 2 and 4 will be deactivated more than position 3. Recall that positions 2 and 4 are often referred to as the ortho and para positions and position 3 is often called the meta position.

We can summarise the above by saying that:

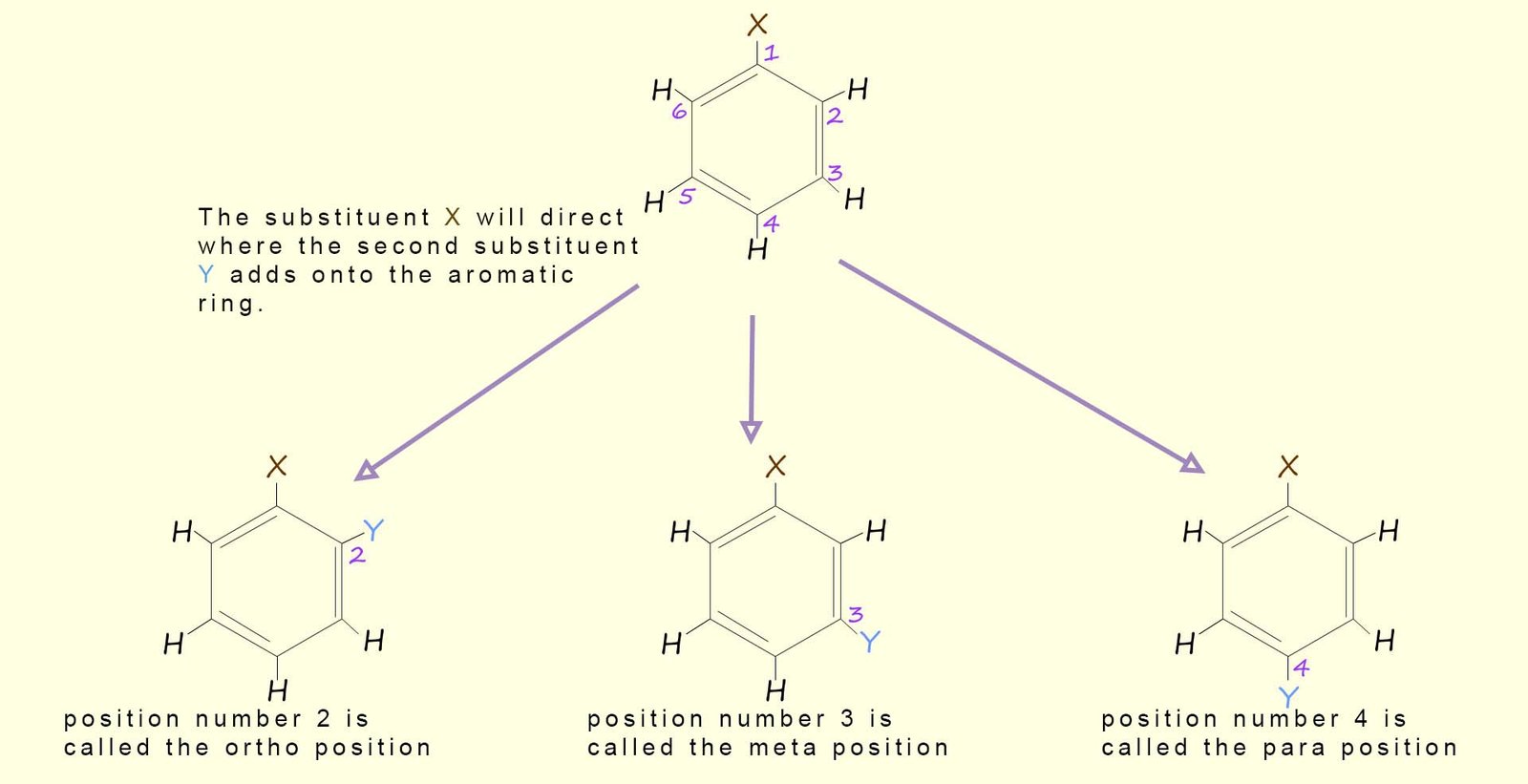

The placement of a second substituent (Y) onto the aromatic ring is largely influenced by the substituent (X) already on the ring. The second substituent can be directed to:

or

or

The table below gives a summary of which groups activate or deactivate an aromatic ring and also the positions where any additional substituents will be directed to during an electrophilic substitution reaction.

| Type of Group | Examples | Effect | Directing Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly activating | –OH, –NH2, –NHR, –NR2 | Strong electron donation by resonance | Ortho/Para directing |

| Moderately activating | –OCH3, –OC2H5 | Electron donation by resonance | Ortho/Para directing |

| Weakly activating | –CH3, –C2H5, –R | Electron donation by induction | Ortho/Para directing |

| Weakly deactivating | –F, –Cl, –Br, –I | Electron withdrawal by induction, but donation by resonance | Ortho/Para directing |

| Moderately deactivating | –CHO, –COCH3, –COOH, –COOR | Electron withdrawal by resonance | Meta directing |

| Strongly deactivating | –NO2, –CN, –SO3H, –NR3+ | Strong electron withdrawal by resonance and induction | Meta directing |

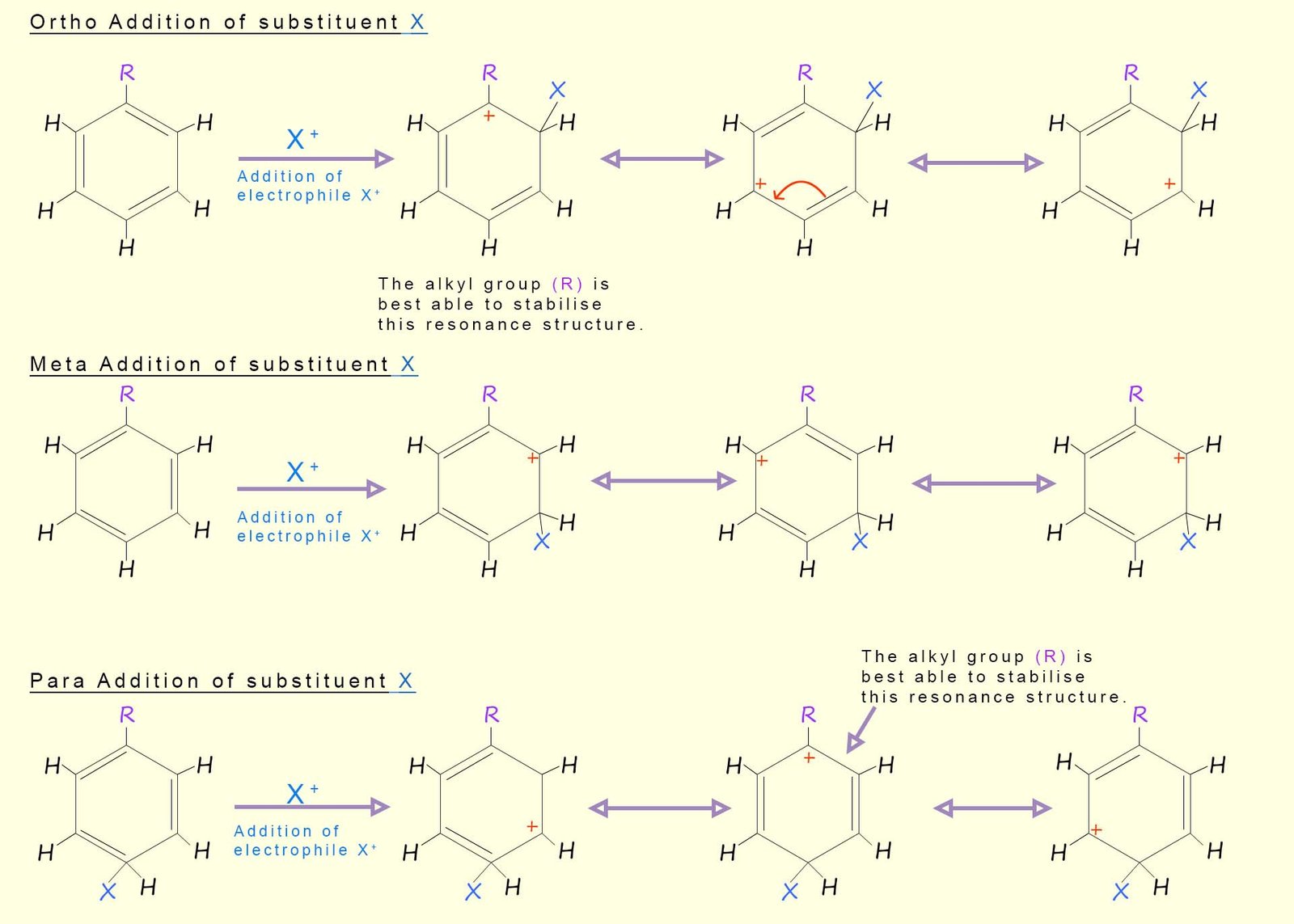

Alkyl substituted aromatic rings

are activated as mentioned earlier by the inductive effects of the

alkyl substituent. However as in the case above further

electrophilic

substitution reactions of alky

substituted aromatic rings tend to occur at the ortho and para

positions. This

is mainly due to the ability of the alkyl substituent

to help stabilise the intermediate carbocations

formed during the electrophilic substitution

reaction most effectively at the ortho and para positions.

This means that these carbocations will

require less energy to form and will therefore have more of a

presence in the overall resonance hybrid structure

(recall that the actual structure of the intermediate carbocation is a combination or hybrid of all

the intermediate resonance structures

and if one intermediate structure is lower in energy it will have

more of an input into the structure of the final resonance hybrid

structure. This is outlined in the

diagram below:

You may wish to practice drawing out similar resonance hybrid structures of the addition of say a nitro group (-NO2) to an activated aromatic ring such as phenol, the resonance structures will be very similar to the ones above, despite the fact that the hydroxyl group (-OH) activates the aromatic ring by resonance and not by induction as was the case with an alkyl group. The ortho and para positions are the only ones which can benefit from the "feeding in" of the oxygen lone pair into the aromatic ring; this means that these position will be stabilise relative to the meta position.

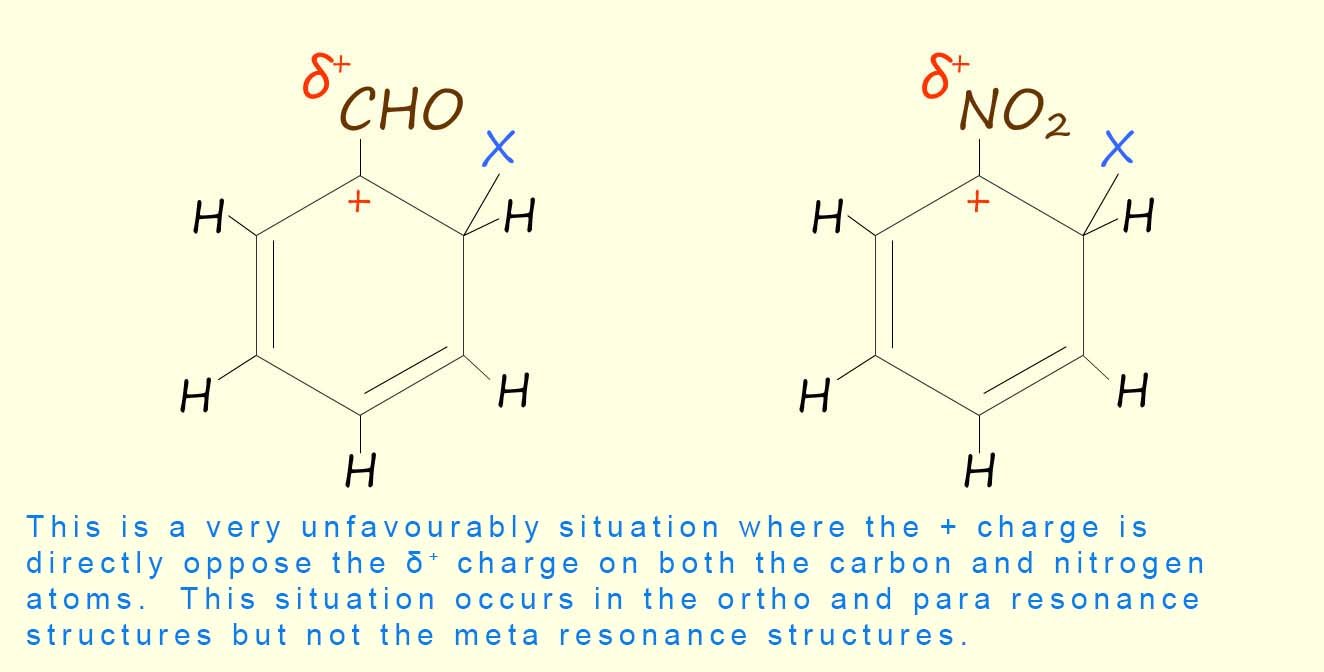

It is also a similar story with meta-directing deactivating groups such as the nitro group or a carbonyl group. However in this situation the most unfavourable intermediate carbocation resonance structure will be the one which places the positive charge in the aromatic ring on the carbon atom directly attached to the carbonyl or nitro group; this would place the positive (+) charge directly in contact with the δ+ charge on the nitrogen atom in the nitro group or the carbon atom in the carbonyl group, as shown in the image opposite. This situation occurs in the ortho and para resonance hybrid structures but not in the meta resonance structures.

It is also a similar story with meta-directing deactivating groups such as the nitro group or a carbonyl group. However in this situation the most unfavourable intermediate carbocation resonance structure will be the one which places the positive charge in the aromatic ring on the carbon atom directly attached to the carbonyl or nitro group; this would place the positive (+) charge directly in contact with the δ+ charge on the nitrogen atom in the nitro group or the carbon atom in the carbonyl group, as shown in the image opposite. This situation occurs in the ortho and para resonance hybrid structures but not in the meta resonance structures.