Aromatic chemistry is a branch of organic chemistry that focuses on the unique properties and reactions of compounds containing flat, planar ring structures with delocalised pi (π) electrons.

Aromatic chemistry is a branch of organic chemistry that focuses on the unique properties and reactions of compounds containing flat, planar ring structures with delocalised pi (π) electrons.

Perhaps the best well-known aromatic compound is probably benzene. Historically, the term 'aromatic' was used to describe substances with sweet smells and fragrances and while some aromatic compounds do indeed have pleasant odours many others are odourless or have very unpleasant smells.

Benzene is perhaps one of the most well known molecules in organic chemistry. Pure benzene is a colourless liquid at room temperature but often appears pale yellow due to the presence of impurities; it has a melting point just below 60C and a boiling point just above 800C.

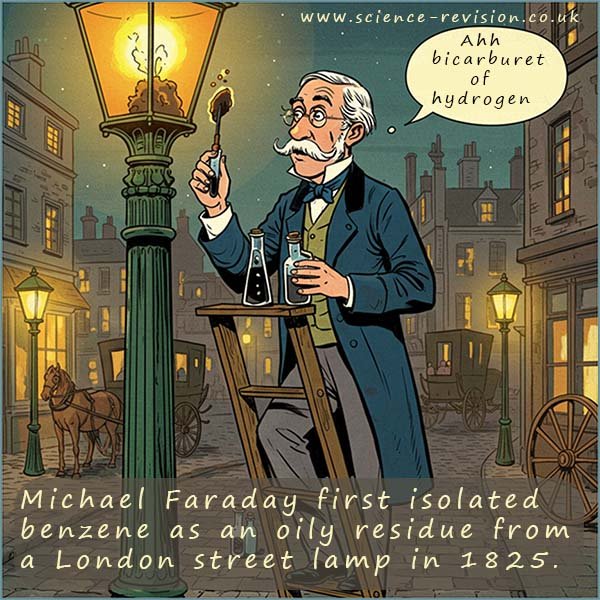

It was first isolated by Michael Faraday in 1825 from the oily residue left in a London street lamp, he called this oily residue "bicarburet of hydrogen". Perhaps one of the reasons that benzene is such a well known

molecule is due to the challenge and difficulties that

arose in trying to figure out the structure of this unusual molecule.

In 1834 the German chemist Eilhard Mitscherlich synthesised a compound which he called benzin by distilling benzoic acid with lime (calcium oxide). Mitscherlich determined that benzin had an empirical formula of CH and a molecular formula of C6H6, this molecular formula clearly suggests that benzin is a highly unsaturated molecule. This compound benzin that Mitscherlich made in the lab was identical to Faraday's bicarburet of hydrogen. The name of

benzin was later ditched in favour of benzene.

In 1845 the English chemist Charles Blachford Mansfield was able to isolate benzene from coal tar and indeed a few years after his discovery he began the large scale manufacture of benzene from coal tar.

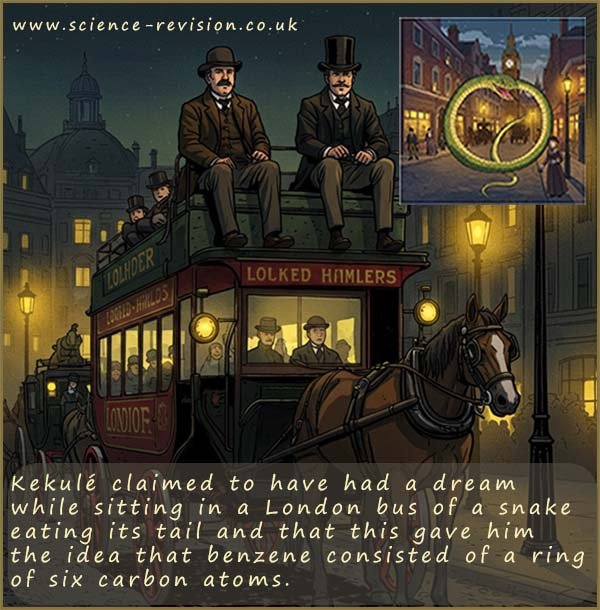

In 1855 Friedrich August Kekulé, a German chemist living in London and working at St Bartholomew's hospital proposed a cyclic hexagon structure for benzene. Apparently,

so the story goes Kekulé was travelling on a horse drawn London bus down the Clapham road in London travelling to visit a friend when he had a dream or a

vision of carbon atoms dancing and joining together to form larger strings or structures and that in his dream the carbon atoms were in motion and turning and twisting like snakes and one of the snakes in his dream was eating its own tail and from this "daydream" or vision" in 1866 Kekulé developed the idea that benzene consisted of a cyclic hexagonal structure which contained C=C and C-C bonds. Now obviously there is no evidence to support Kekulé claims

and indeed there were reports that Kekulé suggested he had another vision or dream in 1861 while he was living in Ghent, Belgium and this dream enable him to develop his theories and ideas on how atoms might join together to form larger structures.

vision of carbon atoms dancing and joining together to form larger strings or structures and that in his dream the carbon atoms were in motion and turning and twisting like snakes and one of the snakes in his dream was eating its own tail and from this "daydream" or vision" in 1866 Kekulé developed the idea that benzene consisted of a cyclic hexagonal structure which contained C=C and C-C bonds. Now obviously there is no evidence to support Kekulé claims

and indeed there were reports that Kekulé suggested he had another vision or dream in 1861 while he was living in Ghent, Belgium and this dream enable him to develop his theories and ideas on how atoms might join together to form larger structures.

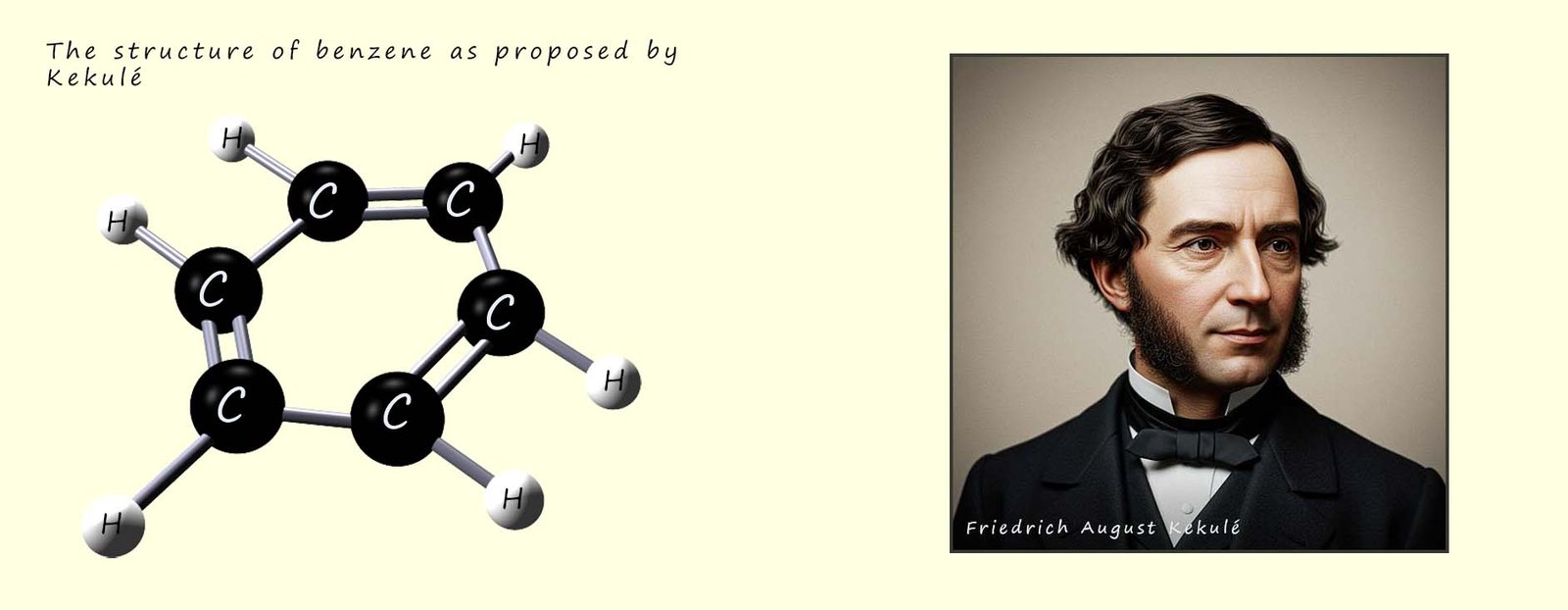

In the mid to late 1800 there was a lot of debate and discussion on the structure of benzene and on the nature of how atoms might join or link together to form larger structures. Many prominent and well regarded chemists had proposed alternative structures for benzene but most of them were rejected and Kekulé’s model was eventually accepted by most, although many chemists still realised that there was something" odd about the structure and reactions of benzene. Friedrich Kekulé model in 1865 suggested that benzene consisted of:

Although the molecular formula of benzene (C6H6) clearly indicated that it was an unsaturated molecule it did not undergo the reactions typical of an unsaturated molecule. You may recall that unsaturated molecules such as the alkenes readily undergo electrophilic addition reactions, so being unsaturated you would expect benzene to undergo these electrophilic addition reactions; however benzene is unreactive towards reagents such as bromine and chlorine that readily react with unsaturated alkenes. Not only that but when benzene does react with bromine or chlorine it undergoes substitution reactions and not the expected electrophilic addition reactions, this clearly suggests that something very strange is going on here!!!

Unsaturated molecules readily undergo electrophilic addition reactions with small molecules such as bromine, chlorine or steam. In these reactions the small molecule simply adds across the carbon carbon double bond (C=C). Since the molecular formula of benzene suggests it is highly unsaturated then you might expect that benzene would readily undergo electrophilic addition reactions- however this is NOT the case. The equations in below show how this electrophilic addition reaction which is typical of unsaturated molecules might be expected to take place, but as mentioned above benzene does not undergo these electrophilic addition reactions.

Benzene despite have a molecular formula that suggests it is highly unsaturated does not undergo electrophilic addition reactions; instead in the presence of iron or a Lewis acid catalyst such as iron chloride (FeCl3) it readily undergoes electrophilic substitution reactions. For example when benzene reacts with chlorine in the presence of iron or a catalyst of iron chloride one of the hydrogen atoms in the benzene ring is replaced by a chlorine atom and the small molecule hydrogen chloride is released. This is outlined in the image below.

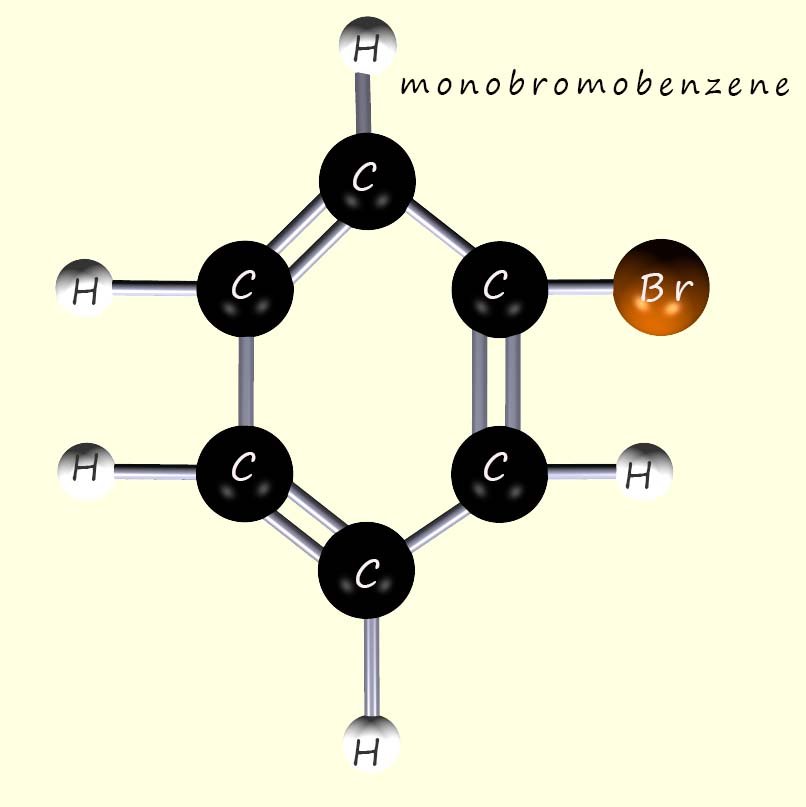

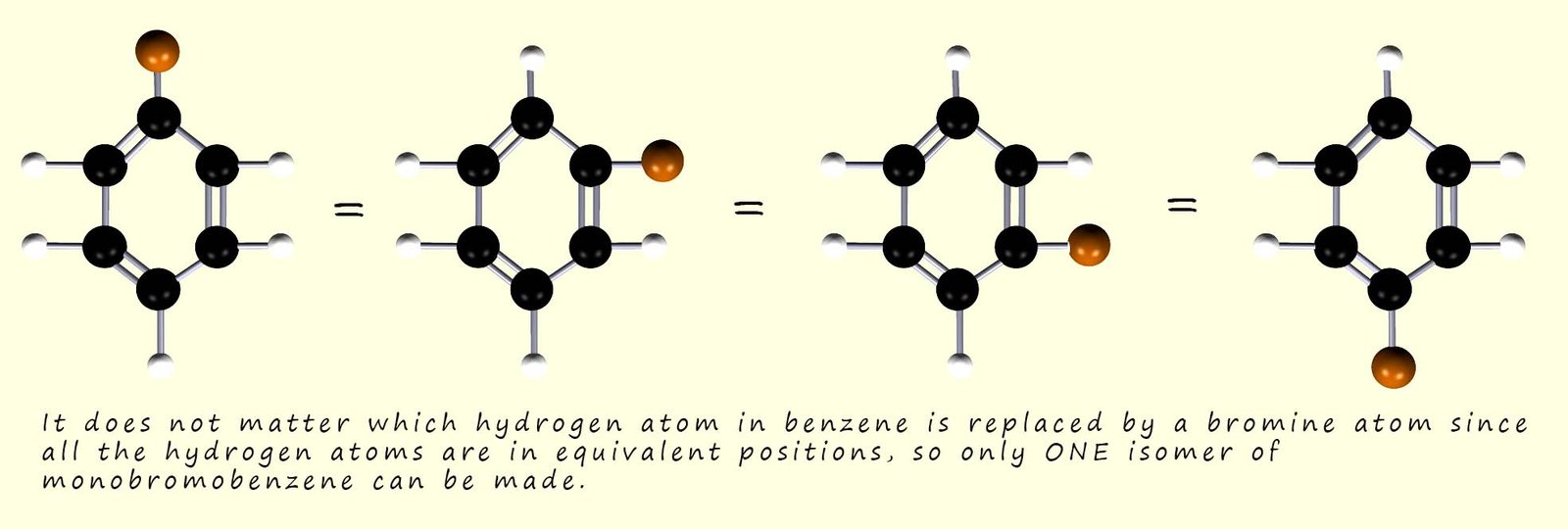

When benzene reacts with bromine in the presence of a Lewis acid catalyst such as iron bromide (FeBr3) then a substitution reaction occurs and one or more of the hydrogen atoms in a benzene ring is replaced or substituted for a bromine atom. What was observed was that for monobromobenzene one isomer can be made since each of the hydrogen atoms and carbon atoms in a benzene molecule are equivalent:

The image below shows how monobromobenzene can be produced by reacting together bromine and benzene in the presence of an iron bromide catalyst.

If more bromine is added then obviously you can replace more of

the hydrogen atoms in a benzene ring with

bromine atoms. While only one monobromobenzene

isomer is produced, in theory four isomers of

dibromobenzene should be able to be produced if

Kekulé proposed structure for benzene is correct.

Now only one isomer of 1,3-dibromobenzene and 1,4-dibromobenzene are able to form according to Kekulé’s proposed structure and these two isomers are shown below:

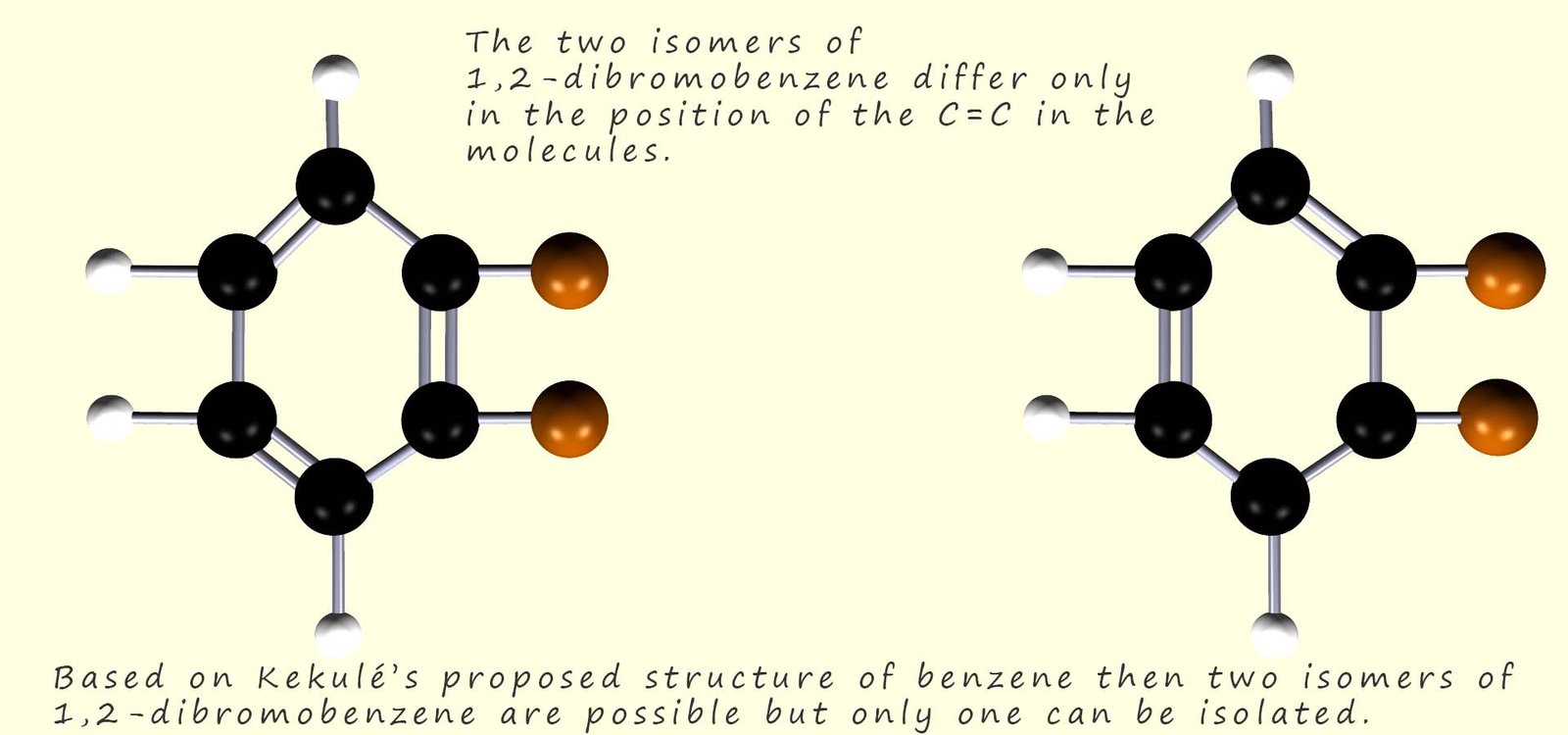

According to Kekulé’s proposed structure for benzene there should be two isomers of 1,2-dibromobenzene, however only one isomer was ever isolated. These two isomers are shown in the image below and you should see that they differ only in the position of the carbon carbon double bonds (C=C).

According to Kekulé’s proposed structure for benzene there should be two isomers of 1,2-dibromobenzene, however only one isomer was ever isolated. These two isomers are shown in the image below and you should see that they differ only in the position of the carbon carbon double bonds (C=C).

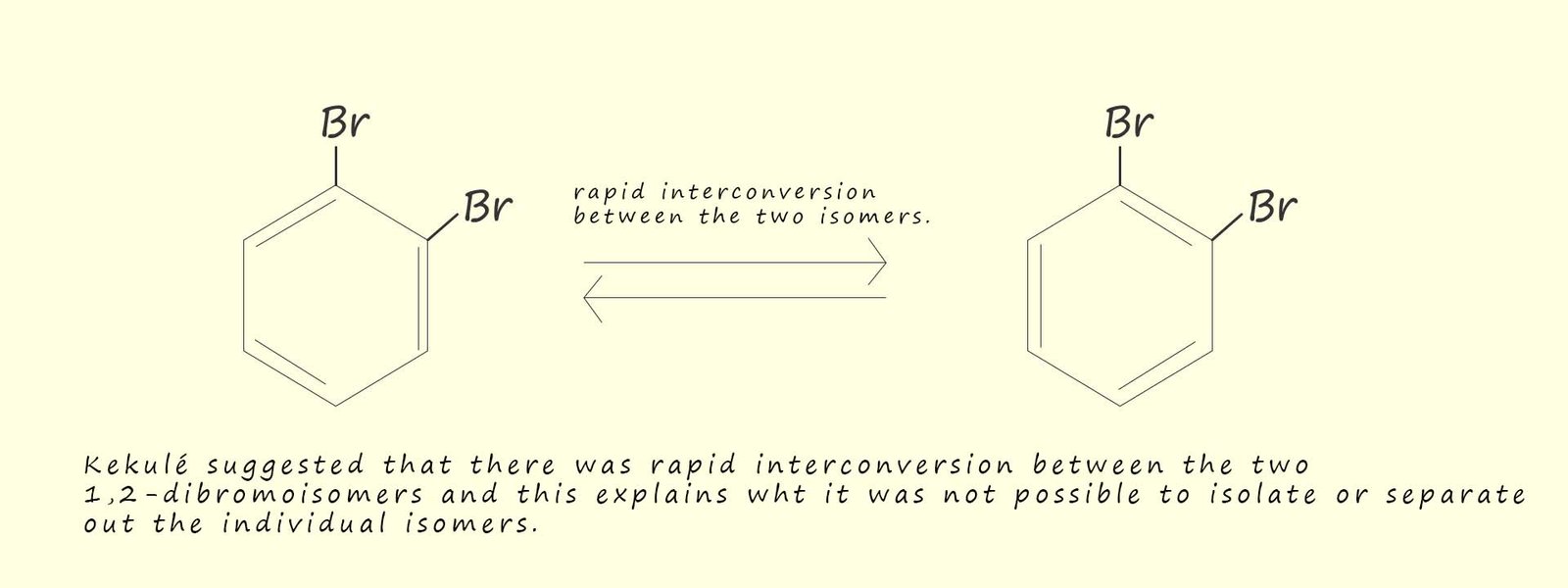

The problem Kekulé had was simple; his theory predicted that there should be 4 isomers of a disubstituted benzene ring such as the ones shown above. However in practice only 3 isomers could be synthesised and isolated. The problem was that only one isomer of 1,2-dibromobenzene could be isolated. You can probably guess what Kekulé's answer to this was! Simple the two possible 1,2-dibromobenzene isomers cannot be isolated because they interconvert rapidly between each of the two distinct isomers. The position of the carbon carbon double bonds is rapidly changing and oscillating between the two possible positions as shown in the image below so it is not possible to isolate any one particular isomer:

You may feel and probably quite correctly that Kekulé's ideas to account for the structure of benzene and his predictions for the number of isomers for the disubstituted benzene rings seem a bit of a fudge. However in his defence they offer an explanation at least for the correct number of isomers for mono and disubstituted benzene rings. The one key point that Kekulé's model fails to address is the fact that benzene's molecular formula clearly indicates that it is unsaturated and yet it fails to undergo the expected electrophilic addition reactions you of unsaturated compounds such as alkenes. Indeed in its reactions benzene undergoes electrophilic substitution reactions and not electrophilic addition reactions and Kekulé's proposed structure for benzene could not offer any explanation for this.

In the early 1930s the theory of resonance was put forward to try and understand why benzene does not undergo electrophilic addition reactions that we might expect from an unsaturated molecule, this is covered in more detail below. For now consider another piece of unusual behaviour that was observed for benzene, that is the enthalpies of hydrogenation of benzene. The hydrogenation of cyclohexene (C6H10) is shown below:

Cyclohexene (C6H10) is an unsaturated molecule containing 1 carbon carbon double bond (C=C). The hydrogenation or addition of hydrogen across the C=C bond is a simple and straightforward reaction and the enthalpy change for this exothermic reaction is slightly less than -120kJ mol-1 (ΔH =-120kJmol-1).

Now if we imagine the hydrogenation of Kekulé's cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene or benzene, as shown below, it would seem reasonable to expect the enthalpy change for this hydrogenation reaction to simply be three times that of the enthalpy of hydrogenation of cyclohexene since the reaction simply involves the hydrogenation of three carbon carbon double (C=C) bonds as opposed to one C=C bond in cyclohexene. However when the hydrogenation reaction is carried out the enthalpy of hydrogenation of benzene is only -208kJmol-1 and not the expected -360kJmol-1, that is -152kJmol-1 less energy is given out than expected. This suggests that benzene is about 150 kJmol-1 more stable than Kekulé's cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene.

If we imagine a simple energy profile diagram similar to the one shown below we can get a better idea of

what exactly is happening during this hydrogenation reaction. If benzene contained alternate

carbon carbon double bonds (C=C) and carbon

carbon single bonds (C-C) as proposed by Kekulé then when the C=C are hydrogenated in cyclohexene H-H and C=C

are broken and C-H bonds are being formed in the product, cyclohexane. The same bonds are being formed and broken

in Kekulé's benzene structure and so we would expect an

enthalpy of hydrogenation of -360kJ mol-1.

However

the

fact that only 208kJmol-1 are released tells us that the bonds being broken in

benzene are NOT simple

C=C. The energy released by forming the C-H bonds in the product and the H-H bonds in

the reactants does not change, the

only bonds which must somehow be different are those in the benzene

molecule. The fact that there is less energy

released means that the benzene molecule

contains less energy than expected, that is it is more stable than expected. This

is shown in the energy profile diagram where you can see that in the second diagram there is

less energy stored in

the benzene molecule so it sits lower down the energy y-axis.

This means that the enthalpy change for the hydrogenation

reaction will be considerable less than expected.

The fact that the bonds in benzene are not C-C or C=C comes from evidence from measuring the bond lengths of the carbon carbon bonds in benzene, the carbon carbon bond lengths in benzene are found to have intermediate length (140pm) between carbon carbon double bonds (135pm) and carbon single bonds (147pm). Now you may recall that pi(π) bonds can form by the sideways overlap of p-orbitals on carbon atoms in molecules which contain double bonds (C=C), as shown in the image below:

In a benzene molecule each of the carbon atoms has one electron in a 2p-orbital. Within the ring all C-C and C-H bonds are formed by the sigma overlap of sp2 hybrid orbitals (hybrid orbitals are not covered/required in the A-level specification), but essentially this results in the formation of a flat ring of carbon and hydrogen atoms. The 2p-orbitals on each of the carbon atoms have lobes of electron density that stick out above and below this flat ring of carbon and hydrogen atoms; as shown in the image below. Now in a normal carbon double bond (C=C) you would expect the p-orbitals on two carbon atoms to overlap and form a pi bond. However in benzene something unusual happens, the lobes on the p-orbitals merge with all the adjacent lobes on other p-orbitals of adjacent carbon atoms. This results in the formation of new molecular orbitals above and below the plane of the flat carbon atoms, essentially we have areas of high electron density above and below the flat ring of carbon atoms. This is outlined below:

To help explain many of the properties of benzene and to help visualise what is happening to

the electrons within a benzene

ring when it undergoes reactions we will use the ideas put forward in

resonance theory. Resonance is a term you will

come across many times when dealing with organic compounds as it is often used to explain the

reactivity or stability

of certain molecules and ions you will meet in the course

of your studies. Resonance is the simply the idea that

in a molecule/ion the nuclei

stay in fixed positions but that the electrons within the molecule/ion are not fixed between the two nuclei in a covalent normal bond but are in fact spread out over more than two atoms. This

is the case with benzene where we have 6 delocalised

pi electrons within the electron clouds or orbitals above and below

the flat ring of 6 carbon atoms.

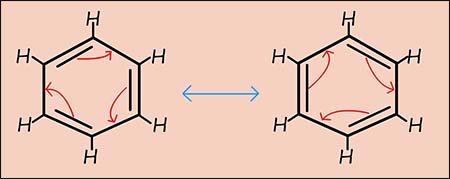

The diagram below shows two resonance structures for

benzene. To draw these two

resonance structures we can imagine that

the carbon and hydrogen nuclei stay fixed but that the

6 delocalised electrons simply spread out over the central ring of carbon atoms. In each of the two

resonance structures which I have drawn there

are carbon carbon double bonds (C=C) and carbon carbon single

bonds (C-C), now from our discussion above we know that in reality these bonds do NOT exist since

all the carbon

carbon bonds in benzene have the same length, intermediate

between double and single carbon bond lengths, but how would or could

you draw a molecule to show this?

The double headed arrow between the two different resonance structures above does NOT MEAN that the two molecules oscillate backwards and forwards between the two different forms, instead it means that the actual structure of benzene is a mix or hybrid of the two drawn molecules. This is very different from Kekulé's model of the benzene structure where there are two distinct forms that oscillate backwards and forwards between the two different molecules. In Kekulé's model there are double and single bonds present within a molecule of benzene.

It was not until the early 1930s when Linus Pauling and others developed the concept of resonance to help explain benzene's structure. Pauling suggested that the structure of benzene was best shown as a series of resonance hybrid structures rather than the model above suggested by Kekulé.

However this is not the end of the story, the Germany chemist Erich

Hückel used the newly developed theory of quantum mechanics to explain the relative stability of benzene. His theory introduced the idea that certain molecules or ions are aromatic. According to Hückel certain flat or planar cyclic molecules or ions with alternating double or single carbon bonds; that is a conjugated system; and which contain delocalised pi(π) have enhanced stability due to resonance, this perhaps would be a more modern way to describe a molecule as being aromatic rather than the more traditional idea that aromatic molecules have pleasant aromas.

Answer the two questions below to check your understanding of the key ideas covered in resonance, add as much detail as possible and in particular focus on how resonance affects the stability and reactions of aromatic molecules such as benzene.

Resonance means that the true structure of a molecule cannot be represented by a single structure instead the actual structure is an average or hybrid of several contributing structures.

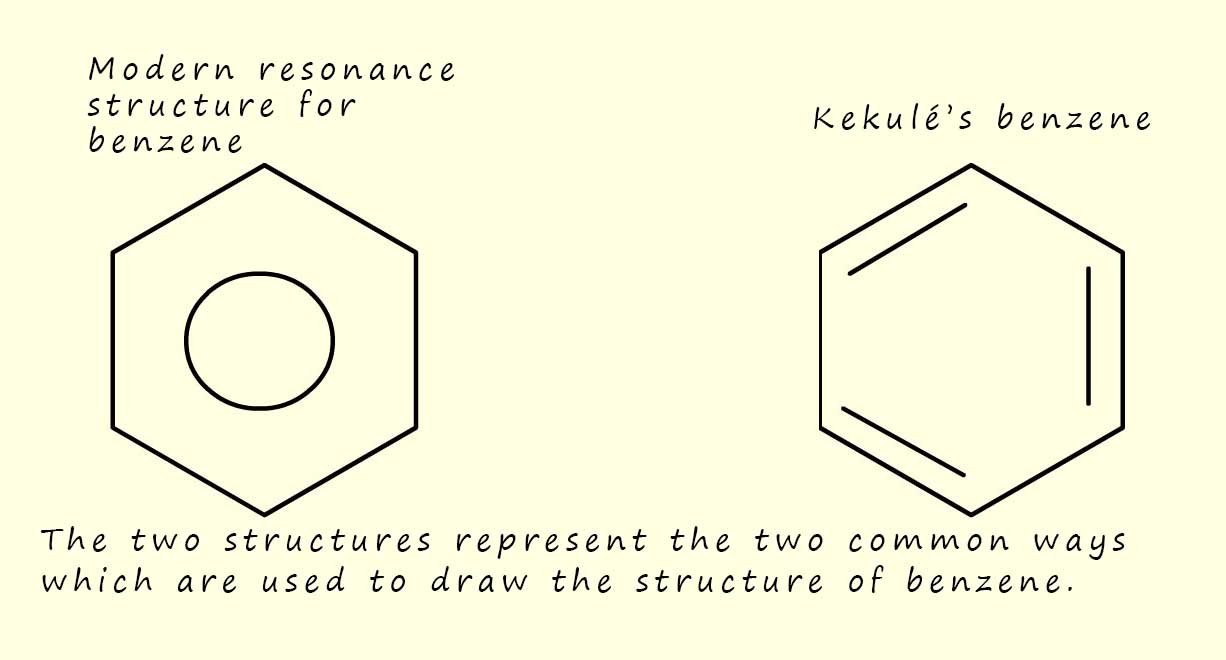

Kekulé Structures: The most common resonance structures for benzene are the two Kekulé structures (shown in the image opposite), where the positions of the double and single bonds between the carbon atoms are swapped.

It's important to remember that these individual Kekulé structures do not actually exist. Benzene is not constantly flipping between them and the actual structure of benzene is a resonance hybrid of these two Kekulé forms. This hybrid is often represented by a hexagon with a circle inside, this circle represents the delocalisation of the six pi(π) electrons from the 2p-orbitals on the carbon atoms.

The spreading out the six pi (π) electrons over all six carbon atoms in the benzene ring lowers the overall energy of the molecule.

The spreading out the six pi (π) electrons over all six carbon atoms in the benzene ring lowers the overall energy of the molecule.

This makes the molecule more stable than if the electrons were confined to specific double bonds. This extra stability is the resonance energy.

One consequence of all the pi(π) electrons being delocalised across all six carbon-carbon bonds is that they will all be identical in length, intermediate between a single and a double bond carbon-carbon bond.

The delocalised pi(π) electron system is very stable. To break this stable system (e.g. in an addition reaction), a significant amount of energy would be required, making addition reactions less favourable. Instead, benzene and other aromatic molecules undergo electrophilic substitution reactions which maintain the delocalisation of the six pi(π) electrons and the stability associated with this.To very briefly summarise what we have mentioned above regarding the structure of benzene we can say that:

Resonance also implies stability within a

molecule. The more resonance forms that

can be drawn for a particular molecule the more stable that

molecule is likely to be.

You will often see the structure of

benzene drawn as a ring with a circle in the middle where

the circle represents the six

delocalised pi electrons or as the Kekulé's structure we have used above.

It is a matter of personal choice as to the way you decide to draw the structure of

benzene and other aromatic

compounds which contain benzene rings. Personally I prefer

to use the Kekulé model showing the presence

of carbon carbon double and single bonds, simply because I find it easier to keep track of the

electrons and to follow

where they are going when writing out mechanisms but other people prefer to use the ring with the

circle in the middle. Ultimately the choice is up to you as both models are acceptable despite

their obvious limitations.

It is a matter of personal choice as to the way you decide to draw the structure of

benzene and other aromatic

compounds which contain benzene rings. Personally I prefer

to use the Kekulé model showing the presence

of carbon carbon double and single bonds, simply because I find it easier to keep track of the

electrons and to follow

where they are going when writing out mechanisms but other people prefer to use the ring with the

circle in the middle. Ultimately the choice is up to you as both models are acceptable despite

their obvious limitations.

Match the terms below with the correct definitions by simply clicking on the term and its correct definition.

Complete the paragraph below by filling in the blanks to complete the sentences summarising the structure and reactions of benzene. The words to complete the sentences are shown in the yellow boxes below, simply select the correct word from the drop-dowm menus.