Unsaturated molecules such as alkenes really only undergo one type of reaction -

addition reactions. You may recall from your GCSE science that small molecules can "add" across the carbon-carbon

double bond (C=C) to form new saturated molecules.

For example bromine and chlorine will add across the C=C bond in

unsaturated molecules such as ethene to form a saturated

halogenalkane.

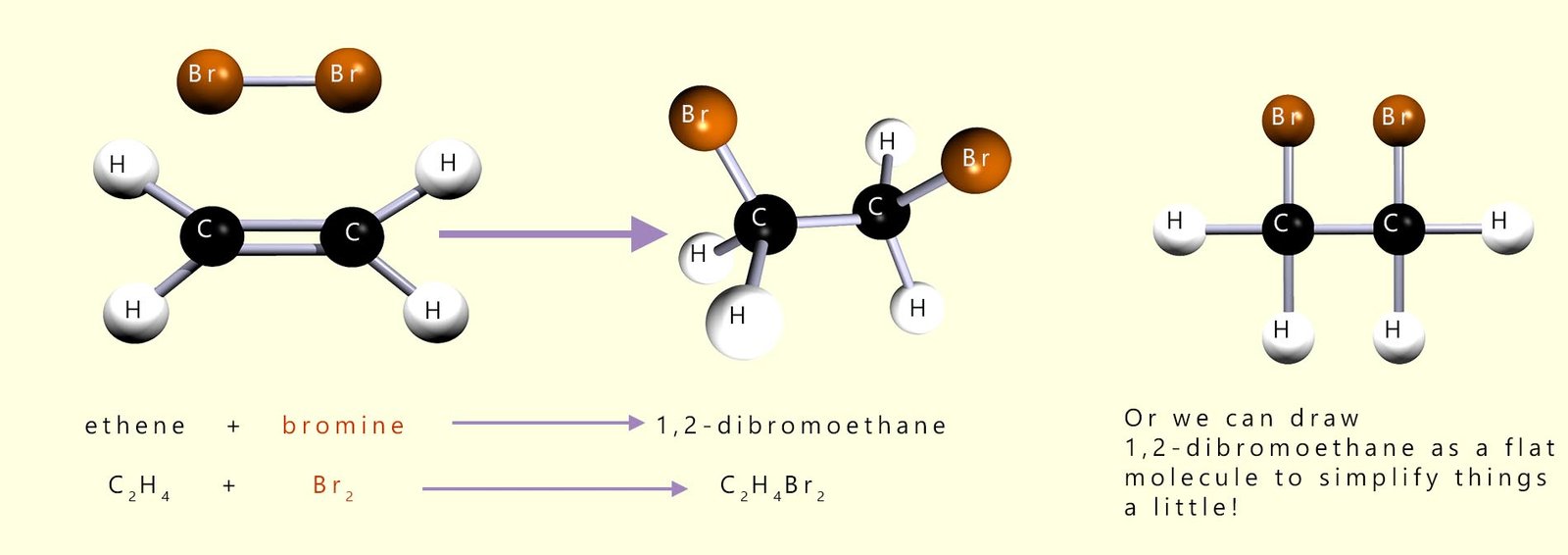

This is outlined in the image below which shows the addition of a bromine molecule across a carbon-carbon double bond (C=C):

A bromine molecule (Br2) can add across the double bond of an ethene molecule to form the colourless halogenalkane 1,2-dibromoethane.

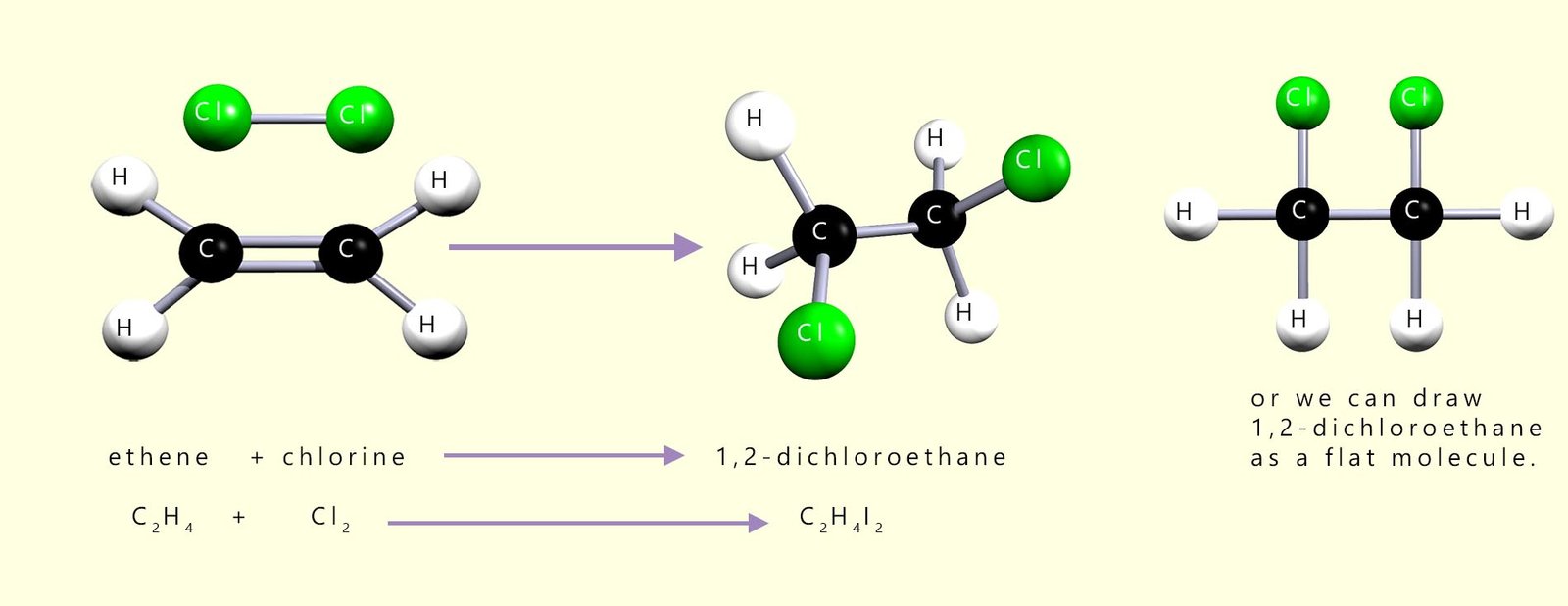

Chlorine will also add across the C=C double bond in an unsaturated molecule in exactly the same way as bromine to form the halogenalkane molecule 1,2-dichloroethane. This is outlined in the image below:

C–I bonds are weaker than C–Br and C–Cl, which helps explain why iodine addition to alkenes is slower and can be reversible.

C–Cl (strongest) → C–Br → C–I (weakest)

(Average bond enthalpies – exact values vary slightly.)

Fluorine (F2) reacts explosively with alkenes such as ethene (C2H4) and other unsaturated hydrocarbons. This can be best described as a very violent, rapid exothermic reaction, releasing a large amount of energy. This reaction can happen explosively under normal lab conditions due to fluorine's extreme oxidising power. Unlike chlorine and bromine, the addition of iodine across a carbon-carbon double bond (C=C) is much slower and may be reversible, because C–I bonds formed are weaker than C–Cl or C–Br bonds.

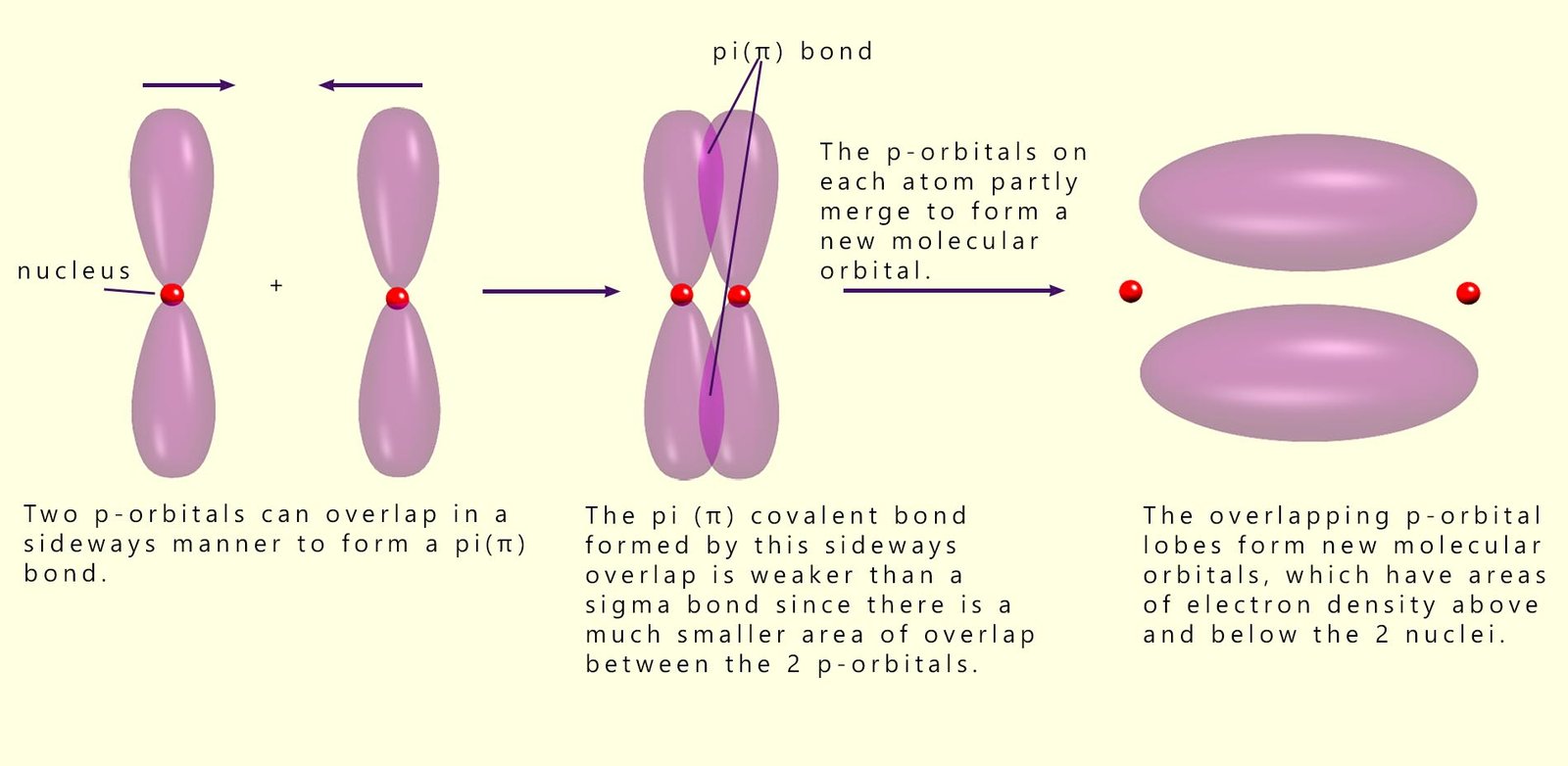

The addition of small molecules such as the halogens, hydrogen halides (HCl, HBr), water or hydrogen to a carbon-carbon double bond (C=C) proceeds by a type of mechanism called electrophilic addition. An electrophile is an electron deficient species, that is to say it is looking to gain electrons and so will be attracted to areas in another molecule where there is high electron density, such as the pi(π) covalent bond in an unsaturated molecule such as an alkene.

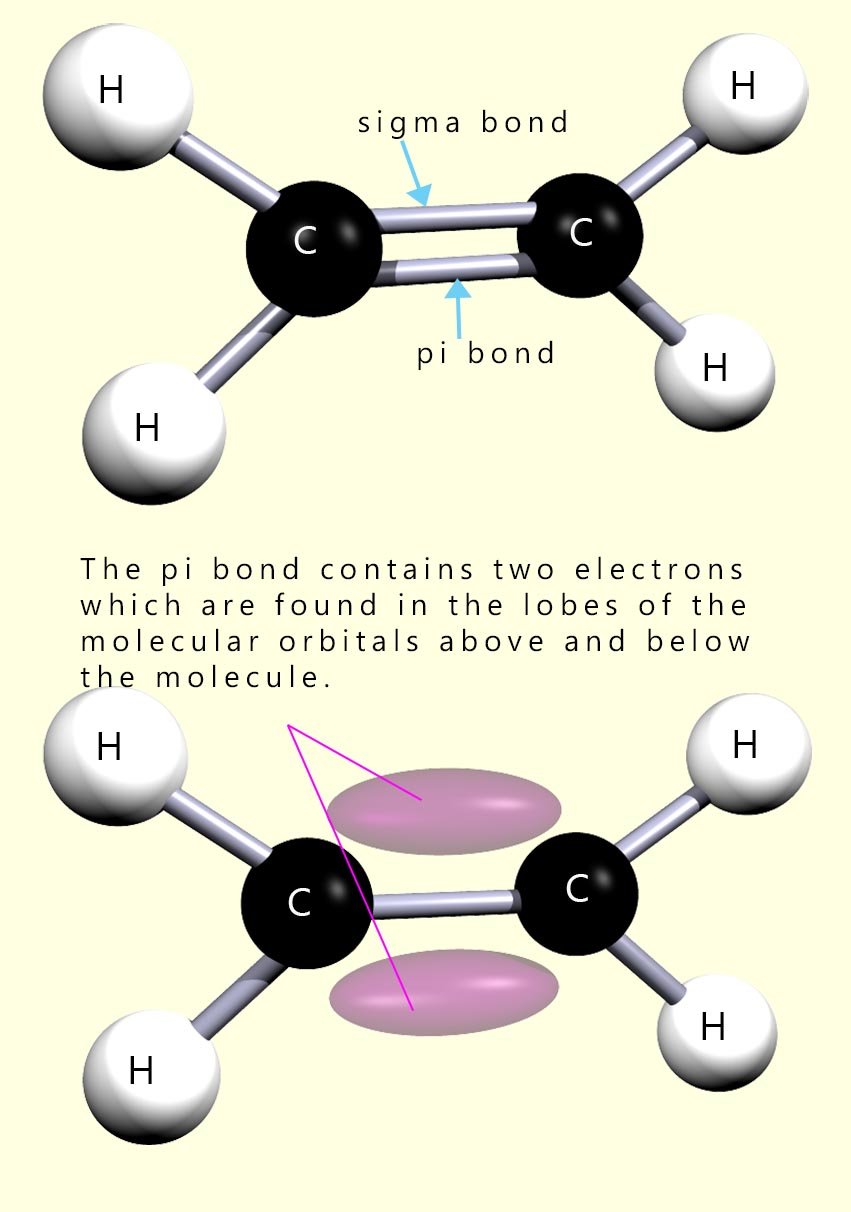

You may recall that a carbon-carbon double bond contains one sigma and one pi bond, and that the pi bond is formed by the sideways (partial) overlap of p-orbitals on the two carbon atoms involved in forming the pi bond. A pi bond consists of two molecular orbitals (lobes) of electron density above and below the two nuclei of the carbon atoms forming the pi bond, as shown in the image below. These two molecular orbitals contain two electrons and are a large target for any electrophile.

It is this area of electron density (the pi bond) above and below the two nuclei which is responsible for many of the typical reactions of unsaturated alkene molecules. It is these two lobes of electron density that are attacked by electrophiles; that is electron-seeking species.

In the molecule of ethene shown opposite we usually just show the pi and sigma bonds as two horizontal lines between the carbon atoms. The problem with this is that it implies that the two covalent bonds are the same, which they are obviously not. For example, the bond enthalpy of a single C-C bond is of the order of 348 kJ mol-1. If the two bonds were identical then we would obviously expect the C=C bond to have a bond enthalpy of double the C-C bond; this is not the case. The bond enthalpy of the C=C bond is of the order of 614 kJ mol-1. So this means that the pi bond is considerably weaker than the sigma bond.

Perhaps a better picture of the bonding in an alkene molecule might be the lower one of the two images shown opposite.

Here the two lobes of the pi bond are shown. These lobes are areas of electron density

where the two electrons needed to form the covalent pi bond

are to be found.

The lobes of the pi bond, sticking out above and below the molecule; leave them open to attack by

electron deficient species - electrophiles. Indeed this is the main type of reaction found in alkenes.

Small electron deficient molecules will add across the C=C bond. These reactions are called

electrophilic addition reactions simply because the small molecules “add” across the C=C bond.

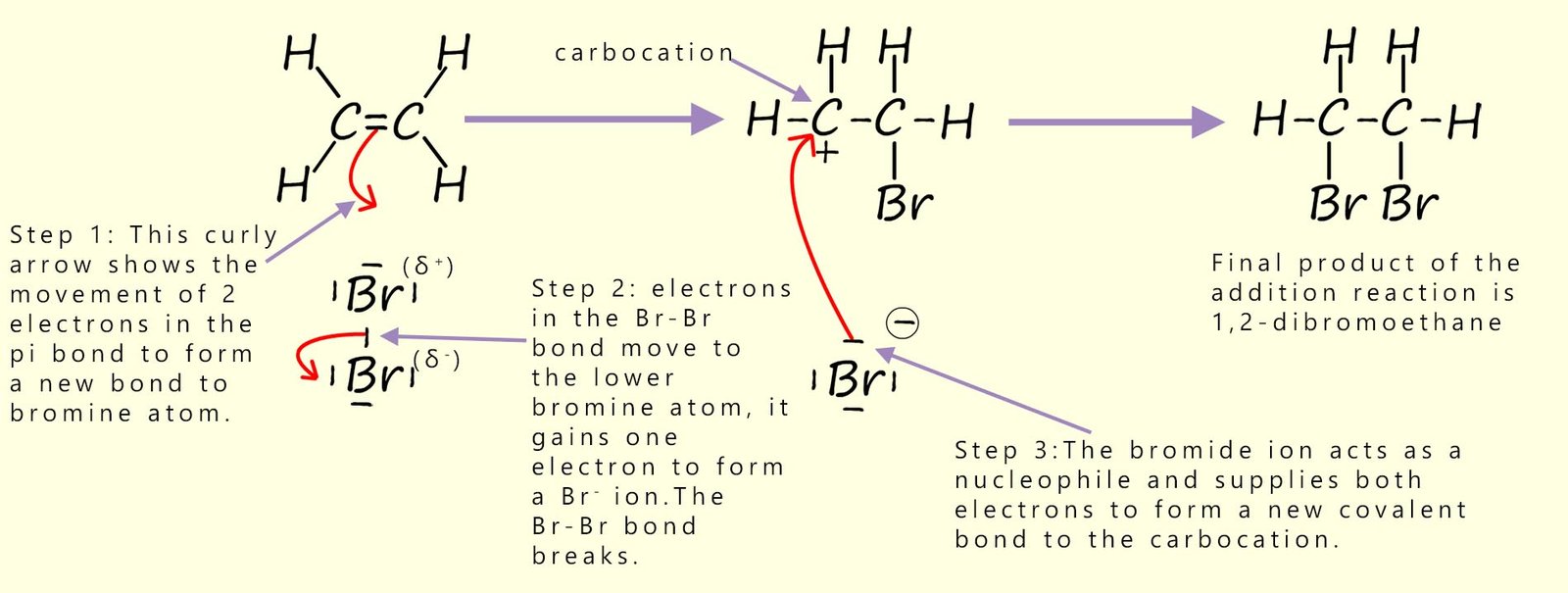

The diagram below gives a step by step account of how a bromine molecule adds to the carbon-carbon double bond (C=C).

The reaction is very easy to carry out in the lab. The alkene can simply be bubbled through liquid bromine

or a solution of bromine in an organic solvent such as hexane.

One thing to be aware of is the position of the curly arrows.

The curly arrows are used to show the movement of a pair of electrons and they give an exact indication of

where any new bonds will be formed. Since a covalent bond requires

two electrons, and curly arrows show the movement of a pair of electrons,

the connection between the two should be obvious.

I would also caution you to take care with where you start and end your

curly arrows, as any examiner will swiftly deduct marks if you get it wrong.

I would ensure that:

When bromine reacts with ethene a colourless halogenalkane liquid called 1,2-dibromoethane is formed. The mechanism for this electrophilic addition reaction is shown below:

Answer the two quick questions below which describe how the curly arrows should be drawn when bromine first reacts with an alkene.

When bromine reacts with an alkene, where should the very first curly arrow showing electron movement start?

Where should this curly arrow end when bromine reacts with an alkene?

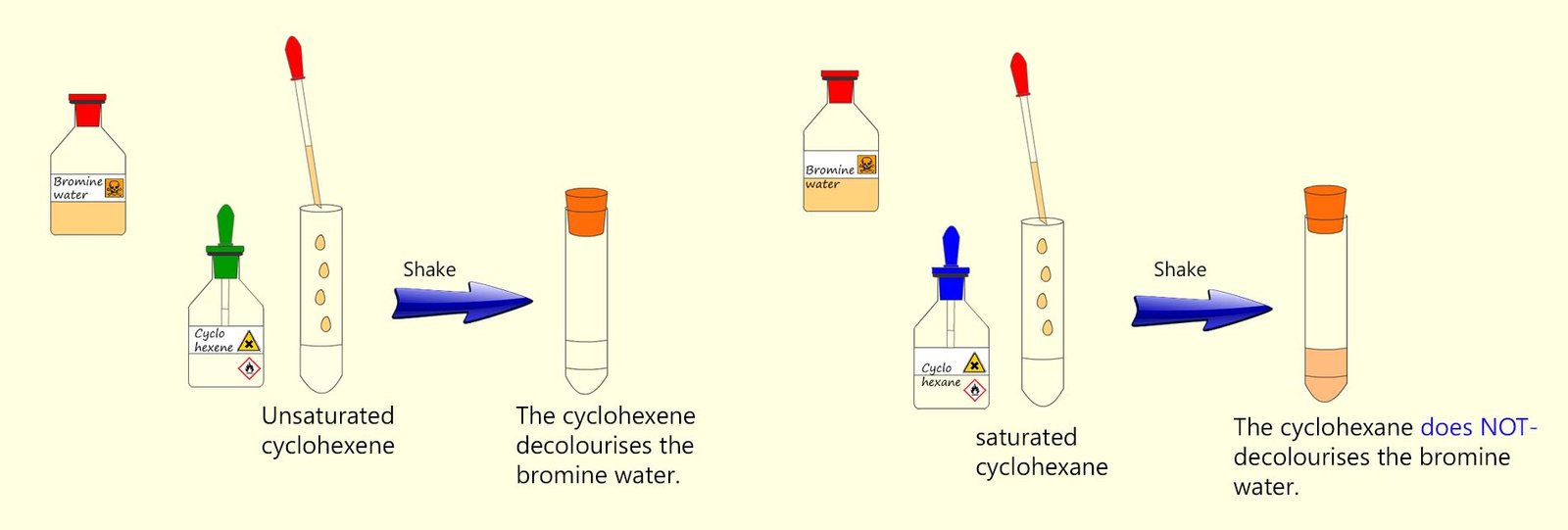

The addition of bromine across a carbon-carbon double bond (C=C) is often used as a test for

unsaturation in a molecule. Here bromine is dissolved in water to form a red-brown solution called

bromine water. When bromine water is added to a suspected

unsaturated substance in a boiling tube and shaken, the red-brown bromine water will decolourise almost immediately.

If the substance under test is a saturated hydrocarbon (an alkane) then there is no decolourisation under normal conditions.

Alkanes only react with bromine via a substitution reaction in UV light (or strong sunlight) but this is a much slower reaction, which is why bromine water is mainly used to test for alkenes.

This is outlined in the image below: the right-hand test tube contains cyclohexane (C6H12), a saturated hydrocarbon,

while the left-hand test tube contains cyclohexene (C6H10), an unsaturated hydrocarbon.

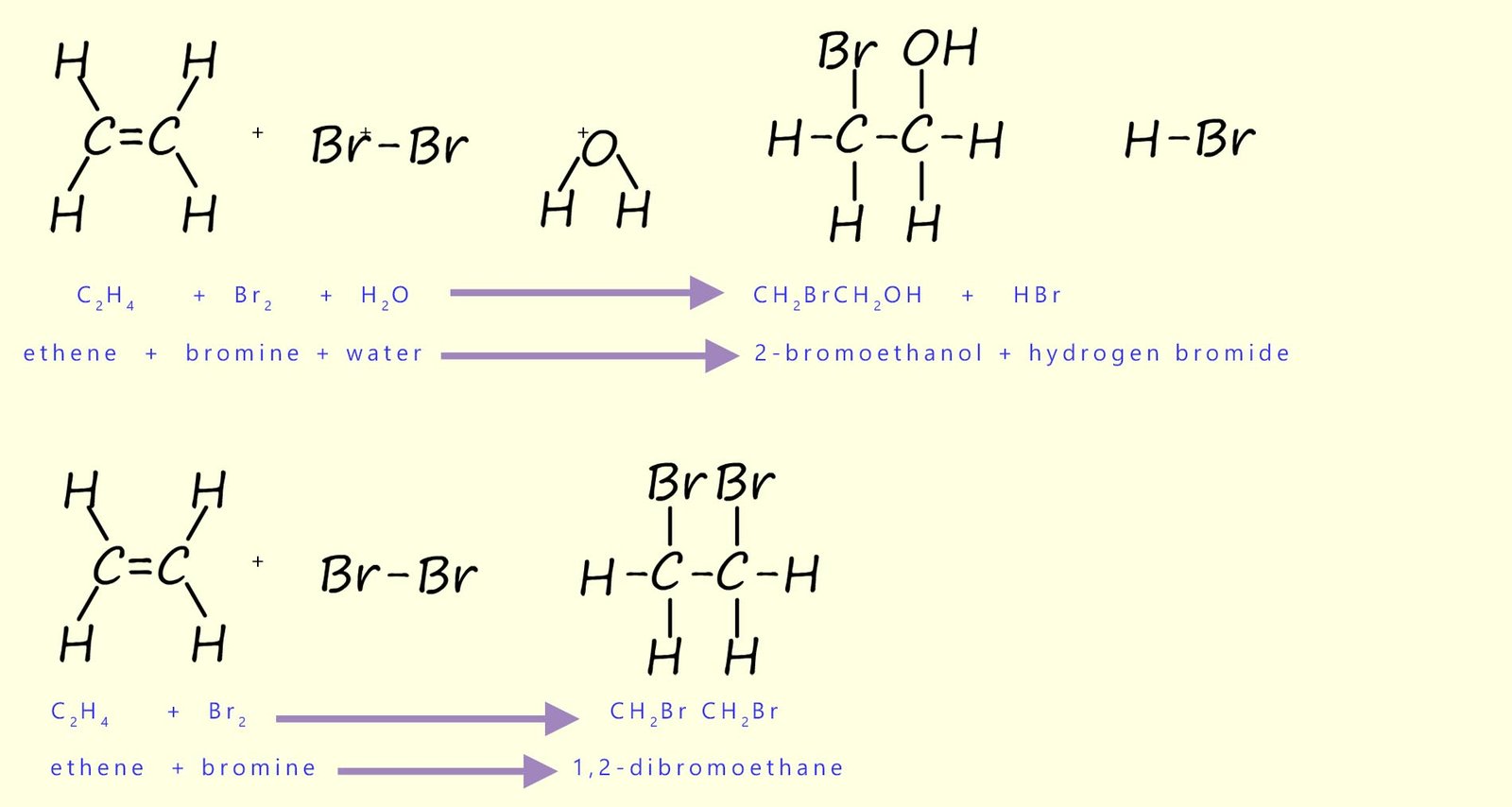

The main product of the reaction of bromine water with the alkene ethene is a colourless solution of

2-bromoethanol (also called 2-bromoethan-1-ol).

You may have expected the product to be 1,2-dibromoethane as was seen above when ethene was bubbled through bromine or a solution of bromine in an

organic solvent.

However; in an aqueous solution water acts as the nucleophile and can attack the intermediate carbocation,

leading to formation of 2-bromoethanol. 1,2-dibromoethane may also form as a minor product.

Equations for these reactions are shown below:

Take a minute and reflect on what you have learned so far and what you know about electrophilic addition reactions, tick the statements below you are 100% confident about.

Before moving on, tick the statements you feel confident about. If you hesitate, that’s a sign to reread the section above.

✅ If you ticked most of these, you’re ready for exam questions. 🔁 If not, scroll back — these are easy marks to secure.

Try the quick quiz below to test your understanding of electrophilic addition reactions.

Decide if each statement is an exam trap or safe. Then reveal the explanation.

1) Curly arrows show the movement of atoms in a mechanism.

2) In electrophilic addition, the electrophile is attracted to the pi bond in the C=C.

3) Curly arrows should start at an atom where a bond will form.

4) Bromine water decolourises when added to an alkene because bromine adds across the C=C double bond.

5) The first curly arrow in electrophilic addition starts at the C=C pi bond.