Higher and foundation tiers

Click a section to learn more.

Crude oil is a mixture of thousands of different hydrocarbon molecules, some of these hydrocarbon molecules like bitumen are very large, while some like those in the diesel fraction produced during the fractional distillation of crude oil are middle sized hydrocarbon molecules while the hydrocarbon molecules that make up the petrol (gasoline) fraction are relatively small hydrocarbon molecules.

However there is a problem with the proportions of each fraction produced during the fractional distillation of crude oil. The more volatile hydrocarbon molecules such as petrol, kerosene and diesel are in high demand as fuels for cars, trucks and planes but Fractional distillation alone does not produce enough of them to meet global needs. Meanwhile, some larger hydrocarbon fractions such as heavy fuel oils and bitumen are produced in greater quantities than are required. The animation on the right shows a break-down of the amount of each fraction produced and whether enough is produced during the fractional distillation of crude oil to meet demand.

The larger hydrocarbon molecules found in fractions such as: lubricating oil, fuel oil and bitumen fractions are produced in large enough quantities following the distillation of crude oil to meet demand for these fractions with extra left over.

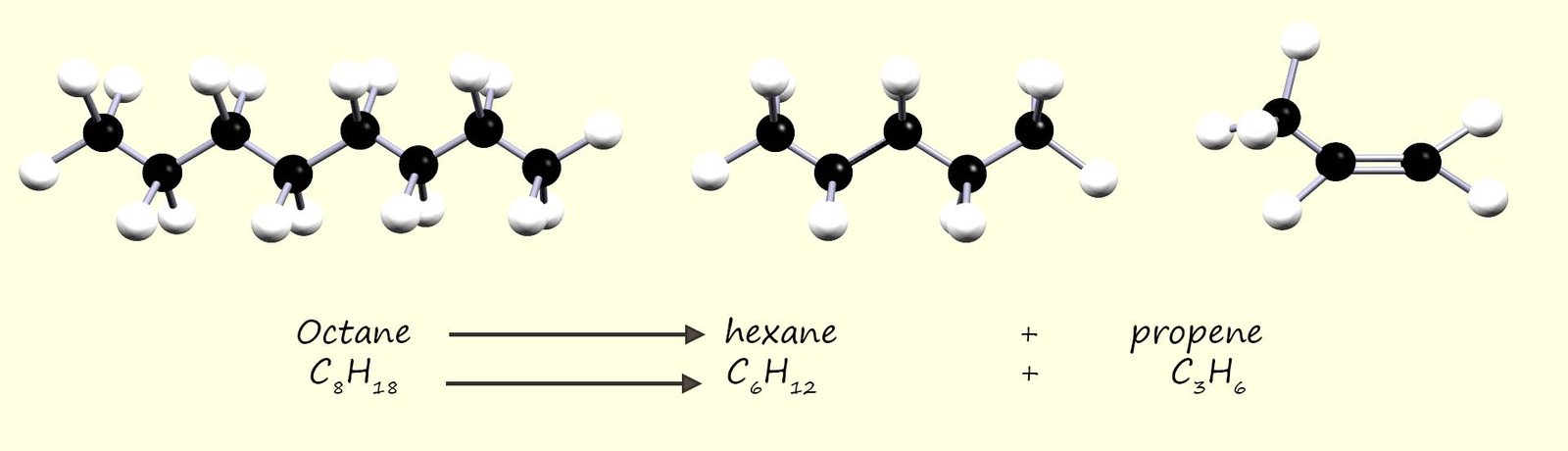

So this leaves a problem; what to do with the "extra" quantities of these large hydrocarbon molecules - the left over's? The solution to this problem is not to simply "chuck away these unwanted large hydrocarbon molecules but to break them up or crack the large hydrocarbon molecules into the

smaller high demand high value hydrocarbon molecules. This process of breaking up these large unwanted hydrocarbon molecules into smaller one is called cracking, for example the image below shows equations for the cracking of the hydrocarbon octane (C8H18) into to smaller hydrocarbon molecules; the saturated alkane hexane (C6H14) and the unsaturated alkene propene (C3H6).

You may notice from the equation below that the saturated alkane is cracked to produce a smaller saturated hydrocarbon and one unsaturated hydrocarbon molecule; this is a common outcome in many cracking reactions.

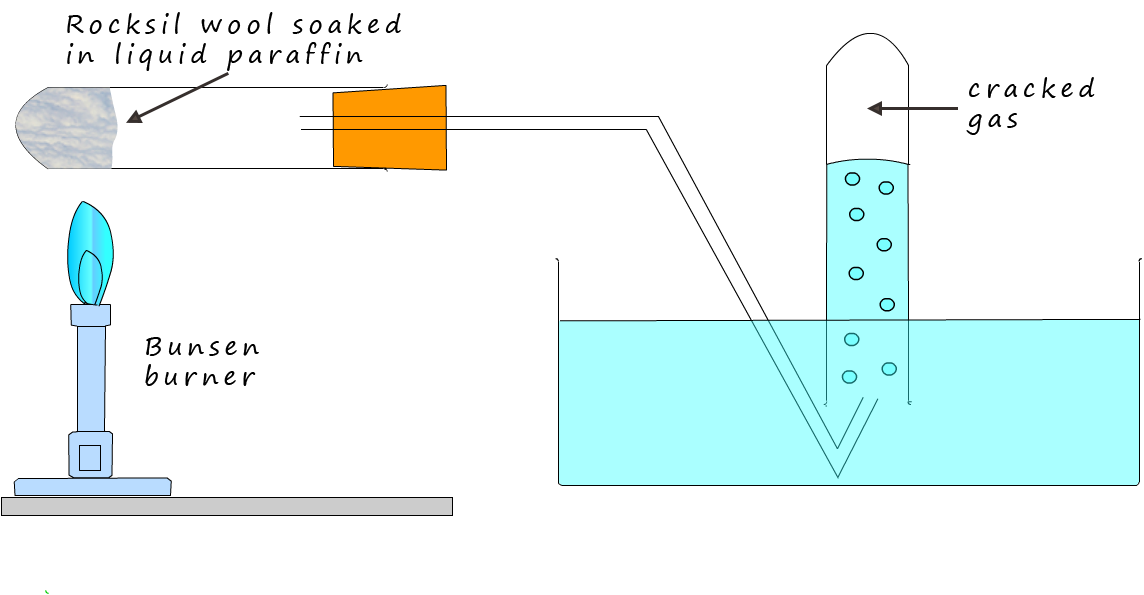

In the science lab it is relatively easy to crack a large chain hydrocarbon into smaller more useful hydrocarbon molecules using the simple apparatus shown below:

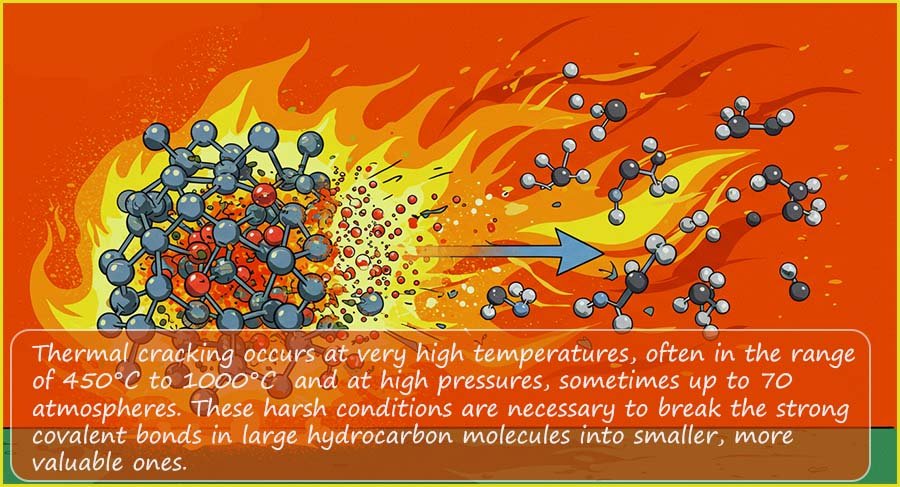

In the image above a few centimetres of heat resistant mineral wool has been soaked in liquid paraffin and then packed tightly in the end of a boiling tube, the liquid paraffin is the hydrocarbon molecule to be cracked. To crack the paraffin molecule you could simply heat it up to a high temperature. As you heat the paraffin molecules they vibrate faster and faster and eventually if they are heated to approximately 7000C the molecules would simply shake themselves to pieces. This would be a simple example of thermal cracking, that is using heat energy to break-up or crack the large hydrocarbon molecules into smaller more useful and more valuable hydrocarbon molecules.

Industrially as well as using a high temperature a high pressure of around 70 atmospheres is also used to crack or break up large hydrocarbon molecules into smaller more useful molecules, this type of cracking using a high temperature and a high pressure is called thermal cracking.

You may recall that a catalyst is a substance that speeds up the rate of a chemical reaction without being used up, a catalyst will also enable the cracking reaction to occur at a much lower temperature; around 450-5000C. This is because catalysts work by providing an alternative reaction pathway that has a lower activation energy. In the image below you can see that the boiling tube contains beads of aluminium oxide which is the catalyst often used in cracking reactions, however in the chemistry lab pieces of broken crockery are often used. In industrial cracking makes use a zelolite catalyts , zeolite is a common mineral containing aluminium, silicon and oxygen (these elements are also present in the broken crockery).

To crack the paraffin molecules into smaller more useful molecules heat up the catalyst for a few minutes with a hot Bunsen flame. Once the catalyst is hot move the Bunsen flame back and forward between the paraffin and the catalyst. The heat from the Bunsen burner will quickly vapourise the paraffin molecules and once the paraffin vapour hits the hot catalyst it will be adsorbed onto the surface of the catalyst and it will be cracked into smaller hydrocarbon molecules. Cracking using a catalyst is called catalytic cracking.

These smaller hydrocarbon molecules are likely to be a gas and they can be collected underwater as shown in the diagram above. The cracked gas is not soluble in water so collecting in this way is an efficient way to do it. It is likely there will be a high proportion of unsaturated hydrocarbons in the cracked gas. You could prove this by simply testing with red/orange bromine water.

Steam cracking is the most common method used

to obtain the unsaturated alkenes ethene and propene, these two alkenes are used to make the addition

polymers polythene and poly(propene) or propylene.

Steam cracking is the most common method used

to obtain the unsaturated alkenes ethene and propene, these two alkenes are used to make the addition

polymers polythene and poly(propene) or propylene.

Steam cracking is a type of thermal cracking. The hydrocarbon to be

cracked, which is called the feed stock;

is mixed with high temperature steam as shown in the image. The steam helps reduce unwanted side reactions from taking place. The

mixture of hydrocarbons to be cracked and the steam are pumped very very quickly through a series of

tubes inside a furnace at a high temperature; typically the mixtures of gases are inside the hot tubes

for between 0.1-0.5 seconds. Cracking happens inside the tubes and the cracked gases leave the furnace and are

quickly cooled by water in a condenser. The mixture of cracked gases and the steam are separated later

in the industrial process. A basic outline of the steam cracking is shown opposite.

The products of cracking depend on the temperature and which type of cracking is used. However cracking generally produces a mixture of saturated alkanes and unsaturated alkenes. We can show this as:

The comparison table below summarises the key features of thermal, catalytic and steam cracking.

| Feature | Thermal Cracking | Catalytic Cracking | Steam Cracking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Cracking | Thermal | Catalytic | Thermal |

| Temperature | ~700 °C | ~450–500 °C | ~800–900 °C |

| Pressure | High (~70 atm) | Low | Low to moderate |

| Catalyst Used | None | Zeolite / broken pottery | None |

| Main Products | Alkanes + Alkenes | Branched alkanes + Alkenes | Ethene + Propene |

| Used In | Industry | Lab and industry | Large-scale industry |